by ProfDave, ©2022

(Jun. 28, 2022) — From 1917 to 1990 is most of the Twentieth Century. As the French Revolution set the agenda of the 19th century, so the Russian Revolution set the agenda for the 20th – perhaps. Over this period the name, at least, of Karl Marx casts a meta-ideological shadow. We must specify the name, because the variety of interpretations of his thought is almost as broad as the denominational spectrum of Christianity. Marxism was originally conceived as a response to the industrial revolution as experienced in the fully developed West. It was addressed to the alienation, powerlessness, and misery of the new industrial proletariat confronting the seemingly unlimited power and greed of the captains of industry. It offered a scientific analysis, an inevitable revolutionary solution, and a completely materialist (non-theistic) millennium.

But mass revolution did not come to the fully developed world. Class conflict, instead of escalating, was sublimated in trade unionism, parliamentary coalitions, and legislative reforms. The leadership of the proletariat was co-opted into the establishment, with some exceptions, or was smothered by Fascist reactions. The revolution Marx had envisioned never came to be.

World War I seemed to be the beginning of the great conflagration Marx had predicted, a great civil war of capitalism which would end in its destruction. But something else happened instead. Any textbook gives a picture of early Marxism, the Soviet Union and China under Communism. These notes will simply hit the high points. Then we will propose some questions about the failure of “the new socialist mankind.”

1) Stalin’s Empire

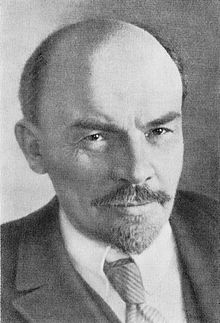

We looked at the October Revolution. Lenin’s Bolsheviks were a minority among exiles from a minority of the Soviets (factory committees) of a minority of the cities in Russia’s infant industrial sector. Russia was just beginning to industrialize, although workers had plenty of grievances under wartime conditions. There was no way that the October Revolution was a mass uprising of the proletariat. Rather, it was a carefully orchestrated coup carried out by a small band of conspirators leveraging forces far larger than themselves. The power behind them – and the mass appeal of their program – was hunger, rejection of the war, and peasant desire for land. Where’s the Marxism? “All power to the soviets” actually meant ad hoc committees in strategic factories and military units led by university educated intellectuals and political activists. The revolution was carried forward by the organizational and military genius of Leon Trotsky and sheer ruthlessness [See Duiker & Spielvogel 684-85].

War Communism, 1918 -1921, sought to transform and modernize the Russian Empire according to Marxist theory. The goal was a society of perfect equality, free from exploitation and coercion, where all would work in harmony for the good of all. But in the meantime, drastic action must be taken by a “dictatorship of the proletariat” to sweep away the old order and establish the new. Revolution by decree was backed up by force in a rapidly developing totalitarian state, wherever the Red Guards held sway. The soviets took over the factories but could not run them without management. Eventually, experienced managers were brought back, paired with “political commissars” to assure their strict obedience to the party line. All private property was nationalized and all citizens between 16 and 50 were mobilized for assigned work and issued rations books in compensation [Harcave 530]. The soviets took over military units – with the same result. Every unit had to have an ex-czarist officer with a commissar to watch over his orthodoxy. But the vast majority of Russia’s population was agricultural and Eastern Orthodox Christian, not industrial or military [Harcave 532].

Rural Russia was backward. Medieval serfdom had only been eliminated in 1861, but in such a way as leave the best portion of the land in the hands of the lords and to substitute the village commune for the lord in relation to the rest. “Redemption” payments (for the majority) were to be collected until 1931 and the village, not the peasant, would own the land – and there wasn’t enough for the growing rural population to live on [Harcave 280ff]. What the peasant wanted was enough land to feed his family, free and clear. At first, the Bolsheviks seemed to grant this by confiscating all land owned by nobility, state, and church and turning it over to local committees – who proceeded to distribute it. But soon, Lenin decreed collectivization, replacing the commune with the collective and the village elders with the peasant soviet. The crop belonged to the state and could be requisitioned at will! So why even plant it?

The Russian Orthodox church had been a department of the state since Peter the Great replaced the Patriarch with a committee. Under the Provisional Government, the Patriarchate had been restored, just in time to see the church’s wealth and property confiscated by Lenin. Complete separation of church and state was officially decreed, but complete control remained in the hands of a Kremlin bureau – implacably hostile. Religious services could only be performed by permission of the militantly atheist government. The church’s subordination to the old regime and commitment to the faith itself brought imprisonment and death to large numbers of clergy and active laity. Most monasteries, seminaries, and churches were closed, transformed into warehouses, museums, and other secular uses. The members of the hierarchy were placed in an impossible position of serving simultaneously as leaders of the church and servants of a regime openly dedicated to its destruction. Duplicity was a requirement of office [Hill 71 ff].

The spectacular failure of War Communism had plenty of excuse. Russian industry and economy were already ruined by the war with Germany and Austria. The Civil war crisscrossed the realm with destruction and terror, both Red and White. Bureaucratic bungling wasted what resources remained, and without cash incentive, productivity plummeted. Millions were reduced to an underground economy, stealing from factories to exchange for food peasants had hidden from requisition – despite extreme police measures. Cities were depopulated looking for food. Manufacturing of consumer goods in 1920 was 13% of pre-war levels, and agricultural production 50% [Harcave 544-46, Duiker & Spielvogel 687-88].

The New Economic Policy (NEP), 1921 – 1928, retreated from the doctrinaire application of Marxist theory by permitting private ownership of small businesses and the private sale of farm produce, restoring the incentive and possibility of getting ahead. Agricultural production returned to 75% of pre-war levels and the secondary disruptions of famine were brought under control. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union underwent its first leadership transition from Lenin to Stalin [Duiker & Spielvogel 697].

Josef Stalin (1879-1953) held power for almost thirty years. A convert to Marxism while a seminary student from Caucasian (not USA) Georgia, he rose through the ranks from revolutionary agitator in the oil fields of the Caucasus to secretary of the Politburo by sheer hard work and attention to detail. Trotsky called him “the outstanding mediocrity of the party.” While the other Politburo members debated Marxist theory, Stalin did the paperwork, made the arrangements, drew up the agenda, and handled the personnel details. When Lenin died, he accused his rivals of disagreeing with Lenin. Supported by the new generation of non-intellectual “easternizers” and technocrats, he sided with the left against Trotsky, then with the right against the left, then with the left against the right until all rivals were disposed of and intra party democracy was at an end [Harcave 582-87, Duiker & Spielvogel 697].

Perhaps Stalin’s most remarkable achievement (apart from World War II survival) was the first Five Year Plan, 1928-33. Under his leadership, the Politburo focused its full attention on the internal development of the Soviet Union, of “socialism in one country.” The concessions of the NEP were to be withdrawn. A detailed plan was developed by the State Planning Commission to industrialize the Russian Empire on socialist principles, not in one generation, but in five years! It took two years and six volumes to articulate. General principles were broken down into specific goals and assigned to regions and on down to the local level. It was thorough but decentralized.

In agriculture, Stalin first moved to break the power of the private farmers (kulaks) who had been successful under the NEP, by inciting civil war in the countryside. This led to crop destruction and famine worse than in the civil war period. Perhaps five million died. But agriculture was collectivized.

Industrialization concentrated on heavy industry, built from scratch at the expense of consumer goods and without foreign investment or assistance. This meant great sacrifices in terms of working hours and living conditions, but it brought a 236% increase in production. This was short of plan, but especially impressive considering the rest of the world was plunged into the Great Depression. A second five-year plan followed: central planning and quotas became a permanent feature of Soviet life [Harcave 588ff].

The Constitution of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics looked democratic. By Communist definition it was – all classes participated without distinction at the local level. But there was, of course, only one party, only one set of candidates, only one program, only one ideology, only one secular religion – Communism. It was a totalitarian sort of democracy. Abroad, Communist parties, at the direction of the International, cooperated with socialists and liberals to form governments in France, Spain, China and other places, gaining favorable treatment in the press [Harcave 636-40]. Internally, repression continued. A new level of terror was reached in December 1934, with the assassination of one of Stalin’s friends and a wholesale purge of old Bolsheviks from the party and army. This culminated in public show-trials in 1937-38. The Soviet military was decapitated on the eve of World War II. 15-30,000 officers were executed or imprisoned, including 90% of the generals, 80% of the colonels, and half the officer corps. Even foreign Communist parties were purged of people not deemed sufficiently loyal to Moscow and to Stalin [Harcave 640 ff].

Why was this tolerated? Party members and citizens saw themselves as building a new society. A new elite of a-political technocrats was leading the way. Gains in education, equality of women, health care, and production were visible, even though the lot of the working man and woman was still severe [Duiker & Spielvogel 798-99].

The war brought new demands for sacrifice, but a surge of patriotism and a relaxation of Stalin’s war on the churches. Much of the war was fought on Soviet soil and the Soviet Union suffered the greatest losses, both material and human. After the war Stalin ruthlessly exploited Germany and Eastern Europe to repair those losses, but none paid so great a price as the Soviet working people themselves. By 1947 production had returned to pre-war levels and new five-year plans continued the emphasis on heavy industry and Cold War armaments. The USSR became the second world super-power in competition with the USA [Duiker & Spielvogel 799-800].

Following the death of Stalin in 1953, Soviet leadership, particularly under Nikita Khrushchev (1958-64), sought a new path. While the Soviet Union was doing very well in the Cold War (“We will bury you,” Khrushchev declared, and we were concerned!), economic growth was stagnating in both industry and agriculture, the arms race was expensive, and living standards were still miserable. Five-year planning was compromised by excessive centralization, creeping corruption and bureaucratic bungling. “De-Stalinization,” revised the history books, abandoned the memory of the “great leader” as such, and sought to renew productivity by profit incentives and bringing new lands under cultivation. Promises were made of more consumer goods [Duiker & Spielvogel 800-801].

Leonid Brezhnev (1964-82) followed Khrushchev with greater reliance on the Party and central ministries in an effort to maintain stability. The regime became more and more defensive in its efforts to control dissidents, minorities, and information. The gap between the freedom and affluence of the west and the relative deprivation of the east was shielded by sealed borders, jammed radio and television signals, and a strictly controlled state media [Duiker & Spielvogel 802 ff]. In the summer of 1979, yours truly visited East Germany. One passed from a continual carnival of color in the West through a barrier of barbed wire, machine guns, and dogs into a gray world where people whispered on the streets! Not much of an advertisement for socialism!

2) Mao’s China

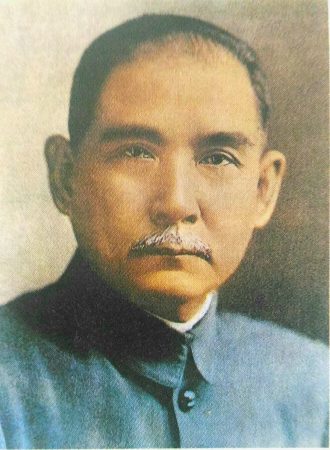

The story of revolution in China goes back to 1911, Sun Yat-sen, and the collapse of the Qing dynasty. The old regime, steeped in Confucian traditionalism, proved unable to cope with the pressures of its own growing population and the need to defend the integrity of Chinese sovereignty against modern industrialized states. The movement to reform, modernize, and industrialize China along western democratic lines was limited to an urban middle class. The “Three Peoples’ Principles” of nationalism, democracy, and livelihood did not sound enough like the “way of Heaven” on the one hand, nor really address the land hunger of the masses on the other. The uprising of 1911 fell into the hands of conservative General Yuan Shikai, as we have seen, and the Republic failed to fulfill its promise [Duiker & Spielvogel 652-655, 716].

In the twenties, two other radical movements were alike identified with small urban minorities: the Chinese Communist Party and the New Culture Movement. Both emanated from Peking University and rejected China’s Confucian heritage for different western ideas. Marxism had some traction among the urban industrial workers in Shanghai and a few other cities, but neither movement had mass appeal [Duiker & Spielvogel 716].

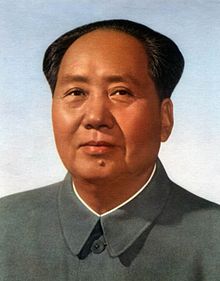

After the death of General Yuan in 1916, the Republic descended into an anarchy of competing regional warlords, exploited by Japanese imperialism. Under Lenin’s direction the CCP allied with Sun Yat-sen’s Nationalist Party (Kuomintang) in 1923. General Chiang Kai-shek succeeded to the leadership of the movement in 1925 and gained military control of most of China. Two years later, he turned on his Communist allies, massacring thousands and driving the remnants into the hills. Here Mao Zedong came to the fore, spurning Soviet advice to build on peasant, rather than urban, discontent. Unlike the Nationalists, Mao had nothing to lose by offering to confiscate the landholdings of the rich and distribute them to the poor. Not exactly Marxism – though akin to the NEP – it had the potential for mass appeal that the Kuomintang and the old CCP both lacked. Chiang founded a new republic at Nanjing in 1928 and reunified most of China (more or less), but civil war would continue off and on until 1950 [Duiker & Spielvogel 717-19].

-340x450.jpg)

The Nanjing Republic represented the westernized elites of China. Chiang Kai-shek gave allegiance to Sun Yat-Sen’s principles but believed the traditional masses of China were not ready for democracy. They would require a firm military liberation and a period of “political tutelage” during which dissent would have to be curbed. He promised land reform, but western principles of law and property did not permit the drastic action that Mao offered. He sought to industrialize and modernize China but took charge on the verge of the Great Depression, was preoccupied by civil war, and then came World War II (starting in China in 1937). Military expenses consumed most of the Republic’s resources. He tried to draw on both Confucian and Western democratic values, while behaving much like a military dictator in practice [Duiker & Spielvogel 719-22].

World War II had been brewing since 1931 when Japan had seized Manchuria and set up a puppet state – in defiance of the League of Nations. Even further back, in the wake of World War I, Japan had succeeded to German interests in East Asia, including the Shantung peninsula. Japanese encroachment and aggression continued. Because of the Communist menace, Chiang Kai-shek was reluctant to confront Japan, but when they seized his capital, he could not reasonably back down. At first, Japan saw its Chinese adventures as primarily preparation for the invasion of Siberia, but when Hitler allied with Stalin in 1939, they turned southward toward Indochina [Duiker & Spielvogel 740-43]. Most of heavily populated eastern China fell to Japanese occupation during the war, but the Chinese Republic continued to hold the interior [See map Duiker & Spielvogel, 746].

The end of the war found the Kuomintang seriously weakened and the CCP much stronger. A large part of northern China and an army of over a million were under Communist control. The benefits of Chiang’s regime, if any, were deferred and his high handed and unsuccessful policies alienated his supporters. On the other hand, by immediately confiscating the lands of the wealthy and awarding them to the poor, Mao rapidly gained support. The USA was unwilling to make more than limited military commitments and was unsuccessful in encouraging compromise. After three years of fighting, Chiang Kai-shek and two million supporters retreated to Taiwan, off the coast, and created there a very successful industrial democracy [Duiker & Spielvogel 777-79].

In the newly united (except peripheral Taiwan) People’s Republic of China, Mao built what he called “New Democracy” – very similar to Lenin’s NEP. As we noted, he used land to buy peasant support and profit incentives to build productivity. Hundreds of thousands were denounced, lost their property, and many their lives. But there were immediate benefits to the many and the general restoration of peace and order. In 1953, the first Chinese five-year plan was launched. Agriculture was collectivized and industry nationalized. Textbooks give the impression that the CCP’s actions were more gradual and popular than Stalin’s [Duiker & Spielvogel 811-13].

The “Great Leap Forward,” 1958 – 60, however, went too far. It created huge super-collectives that did not work. It removed work incentives and attacked traditional family loyalty. Mao did not have anything like the dominance in the CCP that Lenin or Stalin had in the Russian Politburo and he found himself set aside for a time. But he resumed his dominance and revolutionary initiative in the “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution,” 1966 to 1976. Creating an atmosphere of “uninterrupted revolution,’ he mobilized young radicals into a revolutionary army of “Red Guards” who set out to purify China of capitalist and Confucian values. Mao’s Little Red Book took the place of education. It was an indiscriminate and brutal reign of terror [Duiker & Spielvogel 813-14].

Mao’s successor, Deng Xiaoping, curbed the Red Guards and instituted a pragmatic program of “Four Modernizations” (industry, agriculture, technology, and defense). Private initiative was rewarded, and foreign expertise sought [Duiker & Spielvogel 814-16]. There was considerable improvement in material conditions. In 1979, a sweeping population control project, the “one child policy,” was launched to prevent China’s birthrate from exceeding the growth of agricultural production. Allegedly, fertility rate was brought down from 2.9 to 1.7 by 2004, buttressed by forced sterilization and abortion [Hesketh. In 1970, the rate had been 5.9!]. Unintended consequences have been a relative dearth of females and the aging of the Chinese population, coupled with the curtailment of the social security system. Famine was eliminated and the CCP remained firmly in control, despite increasing voices of discontent [Duiker & Spielvogel 822].

3. Whatever Happened to the New Socialist Man (published 2/4/21)

For those of us who lived through the Cold War Era, the collapse of the Soviet Union was a great surprise. Even those of us who were committed opponents of despotism, socialism, and/or atheism – who had argued for decades that such a regime was morally and logically wrong – were unprepared for its collapse. Stalin and his successors had built a superpower, an industrial, military, and scientific colossus equal to or exceeding the best that western democracies could produce – and on the backward ruins of the Russian Empire! While we knew that economically and politically the Eastern block was a bad place to live – after all, the Berlin Wall was built to keep East Germans in – we assumed Soviet citizens were used to it and their endurance was unlimited.

Further (forgive me if there is bias here), Marxist theory had considerable appeal among Western intellectuals. It borrowed the Christian democratic value of equality, so frequently unsatisfied in Western societies, and attached it to naturalistic science, the new worldview of the west. It banished superstition and sentimentality and religious myth. This accorded with the post-Christian yearnings of Western academia for a comprehensive secular ideology. Instead of economics being a science of natural principles given by the Creator or of free but predictable human choices, it became a man-made revolutionary instrument. How could the scientific brain-power of all those central planning technocrats, backed by the full coercive might of the Soviet State and the fervor of the Marxist secular religion – how could it all fail? Was it the hostility of the West (ex Ronald Reagan’s “Star Wars”)? Internal policy failures and mistakes? Or internal contradictions in Communism itself?

Marxism was born as a Socialist response to early industrialization. It built on the exploitation of the working class by the organizers of industrialization on the one hand and the real suffering and relative jealousy of voiceless masses on the other, in the expectation of class warfare. Where the working classes found a voice in labor unions and the political process, however, “class warfare” became limited to rhetoric (in Europe) and/or forgotten in “the American Dream.” Imperialism and World War I only seemed to fulfill Marxist prophecies – they really had little to do with economics. Revolutionary conditions were only a transient phase of industrialization.

In many ways, the Socialist response to land reform – although tangential to Marxist theory – has had more impact. In Russia, in China, and in Latin America the most common concentrations of wealth and of misery were not in the infant industrial sector, but in the countryside. The initial response to Bolshevism and to Mao was the peasant seizure of land from semi-feudal landowners – the promise of enough land to feed one’s family. In both cases, there were self-governing village institutions providing precedents to bridge the gap. But soil and family are basic human needs. Collectivization was accepted or resisted to the extent that it recognized this.

The Socialist response to colonialism also played a very prominent role in the last half of the 20th century. All the colonial powers were Western, Christian, capitalist, and democratic (all the rest having lost their possessions in the war). Russian and Chinese Empires were contiguous. Nationalist leaders were caught in a contradiction between the values of their education, the modernization to which they were committed, and the non-western people they wished to lead to independence. Were they “oreos” – black (or brown or yellow) on the outside, but white on the inside? It didn’t really have anything to do with Karl Marx, but the Soviet model offered an alternative to this dilemma: an anti-western, anti-Christian, anti-capitalist model, independent road to independence – with impressive top-down five-year plans [Duiker & Spielvogel 713-15].

Finally, Socialism, particularly in its Soviet and Maoist forms, confronted the issues of forced modernization and industrialization. Arguably, the Five-Year Plan did work. This was a top-down, command economy, technocracy that accomplished – or seemed to accomplish – in a short time what market forces had not accomplished in the preceding century (for reasons too numerous to discuss here). The social and political costs were indeed enormous. Short term gains were impressive, but ninety years after the revolution Russia was still far behind Western Europe in per capita well being. In China, the jury is still out, but improvement has seemed to come in spite of dogma rather than because of it.

Socialism promised to create a new society, based on a new Socialist mankind. The citizen of this new order would be comrade-centered, not self-centered, socially motivated, not individually motivated. The new mankind would be egalitarian by conviction, untainted by religion, nationalism, racism, sexism or any other kind of myth. This man-made humanity would be utterly rational, scientific and practical. Each person would be hard working and unselfish, totally committed to his/her fellow men/women – to the welfare of all. Such people could participate freely and equally in the direction of their own affairs and in the distribution of the fruits of their labors to their fellows without distinction. Sounds great, doesn’t it?

The Soviet system failed – watch for bias here – because it failed to produce the new mankind. Environment and education repressed, but did not replace nationalism, sexism, and even religious faith. The Communist myth was a poor substitute for Orthodox Christianity as a transcendent moral framework. No way was found in materialism to replace selfishness with the common good. The dictatorship of the proletariat was still a dictatorship, with just about as much inequality, jealousy, and exploitation as the old regime. The repressive state did not wither away. Instead, terror destroyed initiative, even among the technocratic elite, and bred deception, corruption, and mediocrity. In breaking resistance to the will of its director, the Soviet system broke the will of its own people. As the hope of personal (or family) improvement faded further and further into empty promises, the motivation to work with even minimum efficiency failed. Until the 60’s, the Communists were able to hide the relative material and cultural poverty of their own people from themselves, but technological advances in communications began to make this impossible. The Iron Curtain could not hide forever the contrasting conditions of the West. The official modern materialist worker’s paradise was not producing modern material success for its own workers! Spiritual rewards were out of the question. In fact, it was spiritual forces – not just a few dissidents, but large-scale religious resistance – that let the way to general resistance [See Heydt].

Thus the Gorbachev era sought to come to terms with reality too late. The Soviet Union could not afford continued hostility toward the West, let alone a new missile defense arms race. The lid could no longer be kept on the free exchange of ideas, nor on religious expression. The command economy would have to yield to the realities of the market place. A single party system could no longer be imposed by terror and brute force. Once freedom and democracy crept in and the citizens were allowed a voice, it became apparent that the Communist party did not have their support, the centrifugal forces of language and ethnicity could not be suppressed in one federal union, and the USSR, like the Berlin Wall, came crashing down [Duiker & Spielvogel 807-11].

“Red” China goes on, but not as red, early in the new century, as it used to be. The CCP was still in charge, still the dictatorship of the proletariat, but Marxism gave way to state capitalism and there were enclaves of free enterprise reminiscent of the old treaty ports. Western ideas and techniques are being adopted in a pragmatic manner. The internet has made the bamboo curtain irremediably porous and there were sporadic relaxations of police-state repression. Will the transition to a free economy and society – possibly the world’s greatest – be peaceful and gradual? Will the Communist elite be able to share power and/or win free elections? In the last decade this has been reversed, Hong Kong largely absorbed, and Taiwan threatened. Has the Cold War resumed?

Sources:

Duiker, William L. and Spielvogel, Jackson J. World History, 6th edn., Boston: Wadsworth, 2010

Hargrave, Sidney. Russia: A History, 5th edn. Philadelphia: J.B.Lippincott, 1964

Hesketh, Therese, Lu, Li and Xing, Zhu Wei. “The Effect of China’s One-Child Family Policy after 25 Years,” New England Journal of Medicine, 2005; 353:1171-1176. Retrieved 8/8/11 fromhttp://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMhpr051833

Heydt, Barbara von der. Candles behind the Wall. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans,1993.

Hill, Kent R. The Soviet Union on the Brink, Rev edn. Portland, OR: Multnomah Press, 1991.

David W. Heughins (“ProfDave”) is Adjunct Professor of History at Nazarene Bible College. He holds a BA from Eastern Nazarene College and a PhD in history from the University of Minnesota. He is the author of (2020). He is a Vietnam veteran and is retired, living with his daughter and three grandchildren in Connecticut.

MAO ZEDONG was a heroic figure to BARACK HUSSEIN OBAMA. The White House Christmas Tree during the unconstitutional Obama administration had a decorative ball with the face of MAO painted on it. Many pictures of this ended up in the media. I guess Karl Marx was somewhere else (maybe on the wall in the oval office, or in Obama’s suite?). And, guess what, all this time Obama was being supported and controlled from within, i.e. by our own CIA! Just ask General Hayden, Leon Panetta, and especially John Brennan (if you can find them!), And, WHERE WERE PATRIOTIC AMERICANS, MEMBERS OF OPPOSITION POLITICAL PARTIES, AND THE 4th ESTATE GOVERNMENT WATCHDOG MEDIA? For answers to that pesky question, I give you: sworn-to-secrecy pretend patriots and RINOs in the Republican Party (remember McCain, Boehner, Romney and Ryan, McConnell, Reince Priebus, etc?), and phony journalists like Rupert Murdoch, Roger Ailes, Bill O’Reilly, Sean Hannity, Susannah Guthrie (wasn’t she the one who claimed to have held Obama’s so-called Hawaiian birth certificate in her hands?), CNN (Communist News Network), Joe and Mika (her father, Zbigniew Brzenski, was a mentor of Obama), etc. So, is all of this just our country’s “growing pains?” If so, then why are we in danger of becoming a “third-world” country? And, by the way, as it relates to accusations and cries of “racism,” OBAMA ETHNICALLY IS PREDOMINANTLY AN ARAB AMERICAN (94%) AND NOT AN AFRICAN AMERICAN OR BLACK (56%). The CIA was looking for just such a person to represent their globalist, New World Order plans. It’s not that their “spooks” haven’t done similar extralegal things many times in the past! Where is Paul Revere when we need him and other revolutionaries? Just so you will know, I am not threatening anyone or advocating violence! But, that’s just me! Tom Arnold.