by ProfDave, ©2022

(Jun. 14, 2022) — The story of “The Great War,” or World War I, as we have come to call it, is not one of military genius and strategic campaigns but of horror and human suffering. The big picture is one of revolution that touched all of Western civilization, putting to an end the optimism of liberalism, capitalism, and (for a time) democracy and the whole idea of modernity. The war itself was revolutionary in its cultural and (if you will) spiritual impact. The war spawned revolutions, Communist and Fascist, that dominated the world for the next seventy years.

The war of 1914-18 was not the war that anyone expected. Generals tend to prepare for the next war on the basis of the last one, but in this case they skipped over the trench warfare of the Crimean and the last stages of America’s Civil War. At first the Schlieffen Plan (somewhat compromised) seemed to be working. The German army swept through Belgium and into France while the Russians were trying to complete their mobilization. Then the French dug in from the Swiss border to the English Channel and the offensive ground to a halt. A double row of trenches soon stretched the whole distance, guarded on both sides by two new elements: barbed wire and machine guns. Networks of rolls of barbed wire, four feet high (often stacked higher), effectively delayed attacking infantry for execution by the awesome fire-power and accuracy of the machine gun. Increasingly effective artillery preparation only gave notice of impending attack. Aircraft spotters, poison gas, and primitive tanks gave temporary advantages, but only made the trenches more miserable. Men lived ankle deep in mud and blood and excrement, with the stench of rotting corpses, for weeks at a time, summer and winter, unable to peep over the parapet without risk of a hole in the forehead. “Post-traumatic stress disorder” had not been invented yet, but survivors were never the same. Men went mad from the sheer horror of their experiences. Worse still, the Generals, far behind both the battle lines, could think of nothing better than suicidal offensive after suicidal offensive [See also Duiker & Spielvogel 675-79. Be sure to read the excerpt from Remarque].

Two of these stand out. The German general staff picked out the fortress of Verdun, the heavily fortified hinge in the middle of the French line. The idea was not necessarily to break through, but genocide: France would throw everything they had into the defense and be bled white. The Germans took some of the outer defenses in February 1916, and by September the French had lost 460,000 troops (while the Germans took 300,000 casualties) in useless counterattacks. Marshall Petain was given credit for “the miracle of Verdun” – that the fortress did not fall – but at what cost [See also Duffy, “The Battle of Verdun, 1916”]?

The idea of the Somme Offensive, in July 1 to November 18, 1916, was a joint British and French offensive, long planned as a battle of attrition/genocide (to kill as many Germans as possible), but also conveniently to take German reserves away from Verdun. A record 58,000 British died on the first day. On a fifteen-mile front, the allies gained about five miles in five months, suffering about 1.2 million casualties while inflicting half a million on the Germans. This goes down in British memory as “the crime of the Somme.”[Duffy, “The Battle of the Somme, 1916”].

Undeterred by the experience of Verdun and the Somme, the new Commander-in-Chief Robert Nivelle promised to end the war in one grand Napoleonic charge (behind a rolling barrage), involving 1.2 million troops, 7000 artillery pieces, and all the tanks he could find (a clumsy new invention). This grand offensive was launched April 16, 1917, with disastrous consequences. As losses rose to 178,000 in three weeks and the French troops refused to go over the top. The mutiny quickly spread. In effect, they would fight where they stood (or lay), but they would not advance – would not commit mass suicide for nothing. The officers could line them up and shoot every sixth man, but they would not go anywhere. Nivelle was dismissed and Henri-Philippe Petain, the savior of Verdun, was brought in. He tacitly agreed with the troops. France was offensively out of the war. [See also Duffy, “The Second Battle of the Aisne, 1917”]

The situation of the Eastern Front was the same (or even worse) but different. Russia was just too big and its landscape too broken up by marshes, for a continuous line of trenches, but the misery and futility were the same. The Romanov Empire had a seemingly endless supply of manpower (?) but did not have the industry or transportation to support its huge army. They fought without transportation, without supplies, without communications, and without experienced leadership – the trained officers had died early in the war. There are stories of troops going into battle with one rifle for every three soldiers – waiting their turn to pick it up when the others fell. In 1916 they put together a massive offensive against Austria-Hungary (a million casualties), but by the summer of 1917 they were losing more by desertion than by enemy fire – peasant-soldiers voting with their feet. They were needed at home to bring in the crops [See also Duiker & Spielvogel 684].

Political conditions in the Russian Empire were even more delicate. There had been a revolution in 1905, in the wake of the disastrous war with Japan. Rural socialists, constitutional liberals, anarchists and Marxists had impelled Nicholas II to grant civil liberties and create an elected legislature, but by 1907 the army had come home and the legislature had been isolated [Duiker & Spielvogel 575-76]. The war, however, exposed every weakness of the Tsarist regime. The hope of a Constitutional Monarchy faded like the morning mist, distrust of the state was widespread, and conditions grew worse among the vast peasantry and the urban workers who depended on them for food. Even the Tsar seemed more and more ineffective. Faith in the regime was about as low as it could go. Then, in the midst of the crisis, he left the capital (Petrograd) to take personal command of the army. There followed the March Revolution [See also Duiker & Spielvogel 684-685].

The abdication of the Tsar brought about a democratic revolution. The Provisional government, led by liberals and agrarian Socialist Revolutionaries, took over a nation prostrate with war-weariness, failure, and corruption. Starvation was imminent. They appealed diplomatically for an end to the war but accepted the obligations of the previous regime. The war went on. Desertions became a flood. Into this situation came Vladimir Lenin and his Bolshevik exiles, facilitated by a sealed German boxcar (they didn’t want him to get out in Germany) from Switzerland through Finland – or so the story goes.

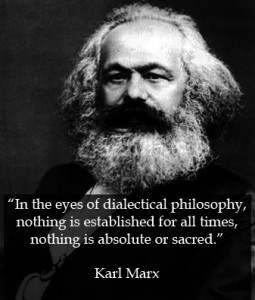

Quick review: Marxist philosophy rested on two principles. 1) The productive event (a person making something) is the basis of society and of history. This is the substructure: all else (ideas, personalities, nationalities, laws, institutions) is superstructure. 2) Society is divided into classes on the basis of their relationship to production. Four processes or stages are at work in industrialization. First, the alienation of the producer (worker) from the means of production (the tools, machines, capital). Second, the concentration of wealth and power in a smaller and smaller number of owners of the means of production (the capitalists). Third, the inevitable polarization of class conflict (fewer and richer owners and more and poorer workers). And finally, the inevitable revolution as the oppressed workers rise to destroy capitalism and usher in a classless society. The means of achieving this end was the education of the working class, followed by a global civil war. All this is driven by the “scientific” dialectic borrowed from Hegel [Thayer, 2/10/69 ff, synopsis of Barzun 156 ff].

Marx’s Communist Manifesto and Engel’s Das Kapital appeared mid-19th century, based on British industrial conditions. But Marxism was too German for Britain. The Fabian Society there represented gradual social reform through cooperatives, trade unions, and Parliamentary action rather than class warfare. Germany had a large and powerful socialist movement, with both Marxist and Revisionist wings. But despite its radical rhetoric, it was committed to parliamentary democracy and resolutely supported the war effort until the last weeks of the war. In France, Marxism had to compete with non-Marxist socialism and anarchism. It was badly split over the Dreyfus affair and over participation in government. Marxism in Russia consisted of an underground fringe and an expatriate community in Switzerland, split in turn between Mensheviks (the minority at one conference) and Bolsheviks (majority?). Lenin’s Bolshevik faction argued that Russia did not have to be industrialized – passing through concentration and polarization phases – to have a revolution if a disciplined elite would seize “the commanding heights” (strategic positions) of industry and power. A revolution in Russia could then spark the world revolution that Marx had promised – the global civil war, in a sense, was already going on in Europe [Craig 301-309 and others].

Lenin was inserted into the elections for the Constituent Assembly, sponsored by the Provisional Government. His “April Thesis,” or platform, was simple but brilliant: 1) peace, 2) nationalization of all land (outbidding the Socialist Revolutionaries for agrarian support), and 3) all power to the soviets (ad hoc committees of workers and soldiers organized in workplaces and military units). An attempted rising in July failed, but the October Revolution (11/7/17 – Russia was on a different calendar) seized Petrograd and several other cities. While only a quarter of the soviets were actually Bolshevik, they indeed seized the “commanding heights,” disbanded the newly assembled Constituent Assembly (majority Socialist Revolutionaries) and proceeded immediately with Lenin’s program [See also Duiker & Spielvogel 684-85].

A separate peace was “negotiated” with Germany at Brest-Litovsk. The Bolsheviks attempted to use it for propaganda, appealing for world revolution, but in the end, it was more like a surrender. Russia was forced back to its 18th century boundaries. Meanwhile, at home, Lenin faced civil war in all directions: monarchists trying to restore the Tsar, minorities trying to win independence, liberals, SR’s, the Czech Legion (nationalist rebels against Austria), Allied intervention, and an all-out war with Poland. Fortunately for the Reds (as they came to be called), they occupied the center of the realm and were able to defeat one enemy at a time [See also Duiker & Spielvogel 685-688].

The withdrawal of Russia from the war and the substantial end of the Eastern front gave German Generals Hindenburg and Ludendorff respite for one all-or-nothing offensive before American troops arrived in force. With new infantry tactics and troops from the east, they were able to reenact their victories of 1914, advancing deep into France, but not to achieve a knock-out breakthrough. A flood of American war material preceded American troops and brought the advance to a bloody standstill. When the tide started to turn, even though German armies were still deep in foreign soil, the Generals abruptly turned the war over to the new republican government to sue for peace. In the minds of many conservatives, it seemed that the army had been betrayed by the politicians of the left. This sense of betrayal, however unjustified, was the source of more revolutions to come [See also Duiker & Spielvogel 688].

Sources:

Barzun, Jacques, Darwin, Marx, Wagner. New York: Doubleday, 1958.

Craig, Gordon A. Europe since 1815. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1961.

Duffy, Michael. “The Battle of Verdun, 1916” (2009), Firstworldwar.com, retrieved 7/19/11 from http://www.firstworldwar.com/battles/verdun.htm.

———-. “The Battle of the Somme, 1916” (2009), Firstworldwar.com, retrieved 7/19/11 from http://www.firstworldwar.com/battles/somme.htm.

———-. “The Second Battle of the Aisne, 1917” (2009), Firstworldwar.com, retrieved 7/19/11 from http://www.firstworldwar.com/battles/aisne2.htm.

Duiker, William L. and Spielvogel, Jackson J. World History, 6th edn., Boston:

Wadsworth, 2010

Gilbert, Martin. Recent History Atlas 1860 to 1960. London, WI: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1970.

Hargrave, Sidney. Russia: A History, 5th edn. Philadelphia: J.B.Lippincott, 1964.

Holborn, Hajo. A History of Modern Germany; 1840 – 1945. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1969.

Kieft, David. “Diplomatic History,” lectures at the University of Minnesota, 1971.

Thayer, William. “Cultural and Intellectual History,” lectures at the University of Minnesota, 1968-69.

David W. Heughins (“ProfDave”) is Adjunct Professor of History at Nazarene Bible College. He holds a BA from Eastern Nazarene College and a PhD in history from the University of Minnesota. He is the author of Holiness in 12 Steps (2020). He is a Vietnam veteran and is retired, living with his daughter and three grandchildren in Connecticut.