by ProfDave, ©2022

(Mar. 23, 2022) — [See previous installments in this series here.]

Remember Diocletian last week? He divided the Roman Empire into four Praefectures, taking Dacia (the Balkans) and the East for himself and building a new capital at Byzantium (renamed Constantinople, and today Istanbul) on the European side of the straits between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean (the Bosporus). Constantine completed the process and converted to Christianity. Successors built an impregnable wall on the land side of the city to protect it from barbarian attacks (Bulgars mostly). Unintentionally, this sealed the East off from the West.

Remember Alexander the Great two weeks ago? Greek culture and language permeated the Mediterranean basin and west Asia. Greek was the trade language of the whole Roman Empire. It was also the native tongue of Greek cities and elites concentrated in the East. But Latin was the language of government and of western elites by the time of Constantine. After Justinian, westerners forgot their Greek and easterners forgot their Latin. Byzantium became Greek.

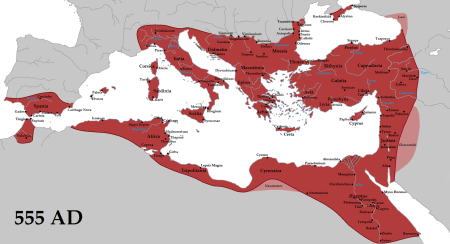

What do we need to know about the history of the East Roman, or Byzantine, Empire? First, it preserved the Roman name until the 15th century. The Western Empire had all but disappeared from the map by 500 AD. The major cities and trading centers of the 6th century were Constantinople, Alexandria and Antioch. Rome has shrunk to the level of Milan and Carthage. Egypt and Syria were particularly prosperous and cultured. Regions that now are mostly desert were then lush, heavily populated farmland (irrigation or climate change?). Compared with any Western city, Constantinople was incredibly wealthy. Although its empire shrank and expanded, trade alone made it an important center of power until the very end in 1453 – and even after!

Secondly, Byzantium operated as a crossroads between Europe and Asia. The height of the Empire was the reign of Justinian, 527-565. He never would have survived the Nika riots if it had not been for his wife Theodora, who was determined to die in purple rather than in exile. He reconquered Italy and the western Mediterranean, built the Hagia Sophia (one of the greatest and most beautiful churches in Christendom – now a mosque), and codified Roman Law. Justinian’s conquests did not last. His successors could not hold the west and fight off a resurgent Persian Empire at the same time. This is a pattern of Byzantine history. They were caught between the Avars – and later Bulgars – in the northwest and the Persians – and later Muslims – in the east. It was a cycle of expansion and contraction.

Thirdly, the Byzantine Empire was pervasively Christian. Constantine set the tone. Even though he himself was unbaptised, he convened and chaired the first Ecumenical Council at Nicaea. The leaders of the church from all over the known world were brought together to settle theological problems (particularly articulating the doctrine of the Trinity). He did not promote any particular views. His interests were in securing the unity of his empire. This and future Councils were not entirely successful. They did not secure unity, but divided the world between heretic (Arians, Copts, Nestorians, others) and Orthodox. Fine points of doctrine became associated with political, national and even economic factions until we hear of longshoremen rioting over them (as well as over chariot races). Eventually, “Orthodox” and catholic parted company, too, but it had little to do with Councils.

The divergence of religion and civilization between old Rome and new Constantinople was gradual. Of the five “Apostolic” patriarchs of Christianity (Rome, Constantinople, Antioch, Jerusalem, and Alexandria), four were in the East and thought in Greek. One, the acknowledged first among equals, was in the West and thought in Latin. The East was plagued by violent disagreements over fine points of doctrine, while the Bishop of Rome tended to settle things Roman style: by authority. The strong Emperor in Constantinople appointed and deposed Patriarchs in the east and acted almost as their chairman, while the Bishop of Rome pretty much had to fend for himself, without Imperial help or interference. He organized the defense of the city and negotiated with barbarian kings. “Papa” or Pope was a name for a priest or bishop. It came to be associated mostly with Rome.

The outward face of the separation was a series of technical religious controversies that had more to do with church politics than substance. The iconoclastic controversy initially pitted Greek and western Anatolian interests against iconoclasts (“image smashers”) from further east. Islamic and Jewish criticism may have had something to do with it. Rome intervened to settle the dispute, basically affirming representations of Christ, angels, and saints as aids to worship, not objects of worship. Although something of a compromise emerged, the high-handed behavior of the Roman representatives was deeply resented. Icons became a stylized two-dimensional art form in Orthodoxy: windows into the spiritual world, not realistic representations. In the west, they were visual homilies, tending towards more realism.

The filioque controversy was about an arbitrary one letter change to the Nicene Creed accepted by the Pope without consulting his eastern brothers. These controversies do not do justice to the widening gulf between Greek and Latin Christianity. Indeed, it is difficult for western Christians to understand at all. Our minds look for clear doctrinal and ethical distinctions. There are very few. Both sides hold to the same creeds and morality. It has more to do with worship and piety and what these things mean to the observant. The Orthodox find their identity in being the church that never changed, from apostolic times. Catholic means universal, the church that is everywhere in communion with Christ – and Rome – in a more Latin sense. We probably should maintain a distinction between the undivided catholic church of the 15th century and the distinctive Roman Catholic church of today.

The last straw was a jurisdictional dispute over churches in Southern Italy that used Greek liturgies. It ended in mutual excommunications in 1054. The behavior of Western crusaders, who sacked Constantinople and seized, for a time, the Byzantine throne, made the division bitterly permanent.

Meanwhile, something very important was happening to the north. Missionaries spread to the north and northwest to the Serbs, Croats, and Avars. The Bulgars (Turko-Mongolians) arrived in the late 7th century. Kievan Rus was established among the Slavs. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonian missionaries sent out by the emperor in the 9th century, adapted the Greek alphabet to Slavonic – the origin of the modern Russian alphabet. Vladimir (978-1015), the pagan Viking prince of Kiev, sent out representatives to Islamic, Jewish, German Catholic and Orthodox peoples to choose a religion. They were awed by the “heavenly” atmosphere of the Hagia Sophia and bored by all the others. So Vladimir marched his people into the river and baptized them Orthodox. The thing that seems odd to us, is that Russian society was dramatically transformed by this seemingly trivial event. When Constantinople fell to the Turks, the center of Orthodox civilization shifted north.

David W. Heughins (“ProfDave”) is Adjunct Professor of History at Nazarene Bible College. He holds a BA from Eastern Nazarene College and a PhD in history from the University of Minnesota. He is the author of Holiness in 12 Steps (2020). He is a Vietnam veteran and is retired, living with his daughter and three grandchildren in Connecticut.

Very interesting, thank you.