“IT WASN’T SUPPOSED TO BE ABOUT ME”

by Sharon Rondeau

(Jul. 4, 2017) — Last Wednesday, a hearing in Los Angeles Superior Court, Torrance Family Court, Department J took place in the case of “Michelle Robinson,” who lost custody of her toddler daughter in March 2016 after Los Angeles DCFS received a referral for protection from an LAPD detective.

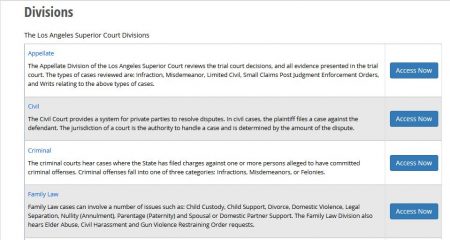

Robinson was seeking an adjustment to the final decision rendered in April by Judge Frank Menetrez of the Edelman Children’s Court, also known as “dependency court,” granting full physical and legal custody to the child’s father, Eric Crutchfield.

Although Robinson had had full custody throughout her daughter’s life until March of last year, a physical altercation between Crutchfield and her on the child’s first birthday, December 20, 2015, ultimately reversed that arrangement.

Robinson considers herself a victim of domestic violence due to what she described as a “vicious assault” in March of 2015 prior to the aforementioned altercation, wherein she sustained a human bite and was treated in a Kaiser emergency room. Earlier in December 2015, only ten days before the most recent assault, she filed for and was granted a restraining order by Commissioner Glenda Veasey in Torrance Court after reporting physical injury in her home with Crutchfield as the aggressor.

Although Robinson filed a police report directly after obtaining medical treatment following the December 20 incident, Crutchfield did not file a complaint against her. After LAPD Detective Sean Horton became involved, Robinson said, her complaint was ignored, and a police report signed by Crutchfield “after the fact” was produced, then provided to DCFS to justify the child’s removal from Robinson’s home.

“He’s the one who inflicted the injury. He didn’t want to file a complaint because he didn’t want to be outed,” Robinson said. She believes that Horton took on an advocacy role rather than simply investigating her complaint.

Robinson is now facing prosecution on a charge of “spousal abuse,” with her complaint against Crutchfield apparently not prosecuted. An initial court date of June 22 was continued to June 27, then again to July 7.

Court orders issued after the April 25, 2017 contested hearing enforced the decision by Menetrez to award complete custody, including decisions over education and their daughter’s development, to Crutchfield, who reportedly has a criminal history involving drug use and having once been jailed for violating Robinson’s restraining order.

In a final decree on April 25, Robinson was granted supervised visitation for two-hour intervals three times weekly provided that she employed and paid a court-approved monitor. Crutchfield was granted a say over the monitor to be used. With professional monitors costing $50 hourly, the court’s proposed schedule would cost Robinson $300 weekly, or $1,200 monthly. “I just don’t have it,” Robinson, who works full-time, told us on Wednesday after the hearing.

Robinson owns her own home and has raised two older daughters who are now college-age.

The referee in Wednesday’s hearing, Commissioner Glenda Veasey, stated that she cannot override dependency court decisions unless a parent demonstrates a significant “change in circumstance” involving the child or children. “She said I have to go back to Dependency Court, but go back to do what? They closed the case,” Robinson told The Post & Email afterward.

Robinson and Crutchfield have restraining orders against one another and therefore cannot initiate contact. Neither Crutchfield nor Robinson was represented by counsel last week.

Prior to the actual hearing, mediation was provided. “Mediation is required if you request to go to court,” Robinson told us. She said that she told the mediator that she believes her daughter is in imminent danger and emotionally scarred as a result of having no contact with her two older sisters for more than eight months.

“It wasn’t about me; it was about my daughter,” Robinson said. “This quote can be misinterpreted. I said that to mean that Eric made his complaints about me, but my issues were about my baby’s best interest. It wasn’t supposed to be about me.”

Robinson said that as she left the room following the mediation session, she called the mediator’s attention to the fact that she did not inquire further as to Robinson’s expressed fears for her daughter’s current situation.

Robinson’s observation to Court Mediator Karen Nakamatsu was later termed “an outburst” by Veasey, with which Robinson took issue. “I did not have an outburst. What I said, as I was about to leave, was, ‘I told you that my daughter is in imminent danger, and you did not ask me one follow-up question about that.'”

Robinson said she was told that Crutchfield’s complaints against her as communicated to the mediator were that she exhibited “bad behavior” during visits and that he feared she would flee with their daughter to Orange County or to Nevada if given the opportunity. “I have no family in Nevada, and Orange County is only 30 miles away,” Robinson told The Post & Email. “I have no plans to go anywhere.”

Another point Robinson believes Crutchfield raised during mediation was an improper but brief custodial arrangement of their daughter ordered by a judge in Inglewood whose function that day was to simply issue a decision on Robinson’s request for a restraining order.

In the California system, commissioners are not full judges and cannot overrule their superiors. Robinson said through the entire life of the dependency case, she was never assigned a dependency-court judge until the final hearings.

“There was an instance, however, in Inglewood, where Judge Titus overstepped her authority and gave Crutchfield custodial visitation,” Robinson said. Titus additionally denied Robinson’s request for a restraining order against Crutchfield. “She said she didn’t think I needed a restraining order and also assigned custody. She can’t do that; her jurisdiction was over a restraining order. My daughter was only ten months old, and she gave Eric one week on and then alternating weeks. They don’t do that when a child is that young, and she overreached her authority.”

“The next morning, I talked to an attorney friend and immediately went to the family court at Torrance to get an emergency ex parte order. The commissioner undid that order and gave me full custody,” Robinson continued. “They had to take my daughter away from Eric because there was then a restraining order in place. After I called the police, he had to bring my baby back.”

“Inglewood doesn’t have a family court; they cannot make custody orders,” Robinson told us. “Judge Titus knew that she could not make custody orders. But if I hadn’t been told that, I would have accepted it. They prey on people because they don’t know.”

“Neither of us is willing to give. I want full custody and nothing less, and he has full custody now. I can’t afford the visitation. I don’t know if they just expect my daughter and me to reunite 18 years from now…” Robinson said at the end of our interview, her voice breaking.

An appeal of the dependency court’s decision is pending without a set date set as of this writing.

Whistleblower in LA County DCFS Reveals Corruption in Child Kidnapping

http://medicalkidnap.com/2016/04/14/whistleblower-in-la-county-dcfs-reveals-corruption-in-child-kidnapping/

“Medical Kidnapping: A Threat to Every Family in America” at medicalkidnap.com