“ALWAYS BEYOND GOVERNMENT”

by Gunnery Sergeant John McClain, USMC, Retired, ©2013, blogging at Gulf1

(Sep. 28, 2013) — In a column the other day, excoriating the knee-jerk reaction of the left, Dr. Sowell castigated the eager-to-ignore-the-constitution politicians including the illegal alien, who suggested if he couldn’t get Congress to make serious inroads in “gun control” he would simply impose it by executive order.

I generally defer to Dr. Sowell, having enormous respect for his scholarship, his long and illustrious career, and in general, all the things I feel are most important in the discussion of law, order, and Nation, but I can’t abide with one singular aspect of his answer to the reason it is so difficult to amend the Constitution, and whether every aspect of it is subject to change. With the Declaration of Independence, our source of first principle, we must defer to such, when we consider altering our constitution, or we risk violating first principles. We have proven how easy we amend it, when “The People” wish, and we’ve proven the impossibility of doing so when it is not popularly driven.

While I’ve been a “constitutional scholar” since my early childhood, introduced to it at about six and intrigued by its unique standing and statement ever since, I don’t pretend to the scholarship of Dr. Sowell, who was in college while I was in tri-cornered pants. His one statement which challenges my perception was the suggestion that the Second Amendment could be written out of the Constitution exactly as any other aspect of the Constitution could be, and from my own understanding, this is simply not true.

As the Constitution was written, Mr. Hamilton, speaking for “the Federalists,” held sway over much of its final draft and language. He suggested the enumeration of rights in the Constitution would likely ensure they alone would never be considered at all, and attempts to “find,” as the founders intended, would meet strong opposition, arguing even “natural rights” enumerated would be disparaged and efforts to eliminate even them.

The representatives of North Carolina, my home, and Dr. Sowell’s birth state, simply refused to even consider ratifying the Constitution if it did not enumerate, at the least, the most fundamental natural rights, and they were joined by three or four other states.

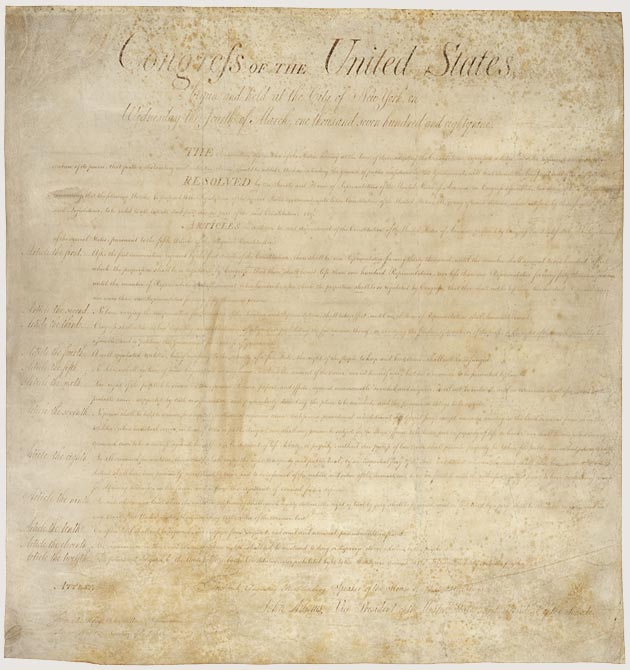

A conference between these representatives and convention leadership, Mr. Madison among them, came to the compromise ofratifying the Constitution with the first issue for Congress the debate over the inclusion of the “Bill of Rights.” As stated, this was constitutional recognition of “natural rights,” the mere statement these rights are recognized by These United States as natural, belonging to all Man, and “unalienable” as stated in our National Creed, our Declaration of Independence, and our founding principles.

“The Bill of Rights” began as a listing of “natural rights” which had been seen by all the representatives as “naturally belonging” to all natural born people, and the enumeration of them, as simply written recognition of self-evident truths.

By this perspective, “The Bill of Rights” was seen as fundamental to our first principles as established in our Declaration, which specifically stated our proper and rightful cause for separating from England, or declaring the violation of “natural rights,” routinely abrogated, the cause for separation.

The installment of ten of the twelve articles in the Bill of Rights was seen and fully intended as exactly enumerating formally-recognized rights belonging to all and securing the fact most “natural rights” remained to be “discovered.” Established in our Creed, they were installed in our “Constitution,” the “contract to form our government,” as a formal measure, established as “unalienable.”

The first purpose of the Constitution, establishing government, and constricting it specifically to exact limits was insufficient; experience had shown exact reference to principles had to be made. The Bill of Rights alone proclaims unalienable rights belonging to all people and is singular in being expansive, rather than constricting, as the entire Constitution is, for controlling government.

The singular meaning of “unalienable,” a word used almost exclusively with regard to “natural rights,” was clearly defined by our founders as literally between Man and God alone, out of reach by any and all institutions of men.

The “Bill of Rights” appears as the first ten amendments of our putative “amendable constitution;” however, their derivation from our Declaration and the means by which they were installed in the constitution denies their being treated as any part of it, but demands they be treated as “predecessors,” as impositions of our Declaration of our rights, as always beyond Government.