by James Lyons-Weiler, PhD, Popular Rationalism, ©2025

(Oct. 2, 2025) — We don’t tend to think about iodine. It’s not glamorous. It isn’t viral. It doesn’t appear in public health campaigns like folate or vitamin D. It doesn’t inspire Silicon Valley startups or make headlines in biotech media. And yet, quietly and profoundly, iodine remains indispensable—essential not just for your thyroid gland, but for nearly every metabolic function, for proper fetal brain development, for reproductive health, and for cellular regulation throughout life.

What happens when we stop measuring it? What happens when we assume it’s there, hidden in salt, in multivitamins, in the sea-scented air—and move on to other public health fads?

A new study in Science, Public Health Policy & the Law makes the case that we may have done just that. And that we shouldn’t have (Hartmann et al, 2025).

Iodine, the Halide Puzzle, and What’s at Stake

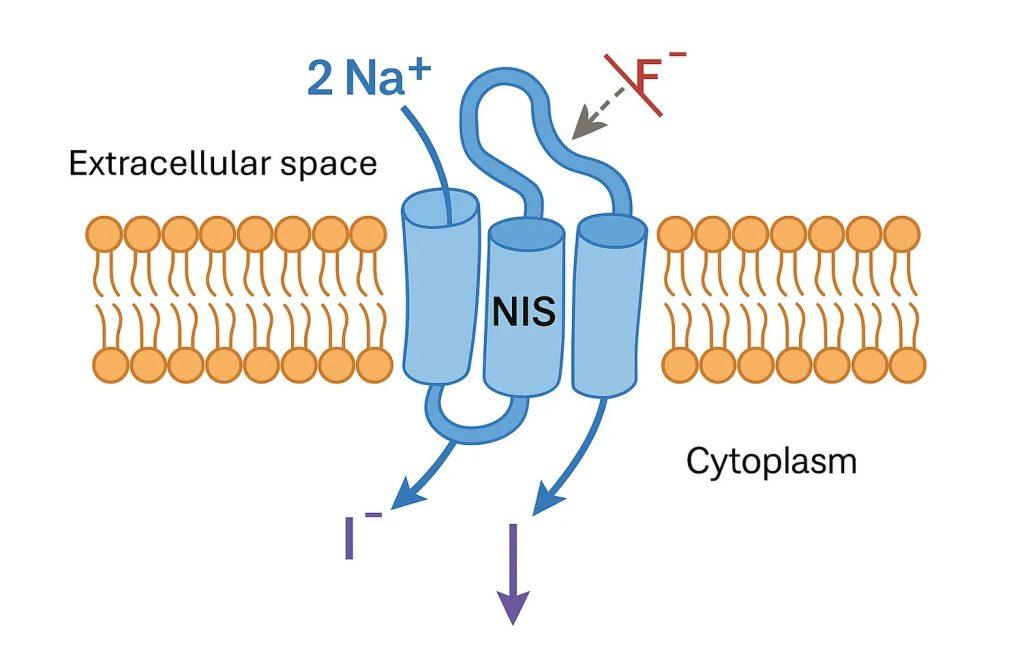

Iodine sits on the periodic table next to bromine and fluorine, elements collectively known as halides. All three are chemically similar, and that similarity creates a problem: they compete. Inside the human body, iodine must be actively transported into cells that need it, particularly in the thyroid, breast, ovaries, and salivary glands. It uses a specific protein transporter—the sodium-iodide symporter, or NIS. But fluoride and bromide can hijack that same transporter, displacing iodine or blocking its uptake.

This matters, because the thyroid cannot function without iodine. And thyroid function governs everything from your energy levels to your mood, weight, heart rate, and fertility. Even mild iodine deficiency during pregnancy is associated with lower IQ in offspring and subtle cognitive delays. In severe cases, iodine deficiency causes goiter, hypothyroidism, and developmental disorders.

The paradox? Iodine deficiency was once declared solved. In the mid-20th century, iodized salt campaigns were widely adopted. For a time, population iodine levels rose, and policymakers moved on. But over the last three decades, quiet declines have been documented in places like the U.S., Europe, and Australia—even among those thought to be safe. And this decline may have accelerated in settings where fluoride is added to water or brominated compounds are present in food, flame retardants, or industrial chemicals.

The study out of Florida doesn’t just revive this concern—it makes it local, testable, and difficult to ignore.

Inside the Brevard County Study

Between 2021 and 2024, a primary care practice in coastal Florida—Iron Direct Primary Care—systematically measured iodine and halide levels in its patients. They didn’t guess. They ran spot urine tests. They measured iodine in the blood. And in some patients, they gave a 50 mg iodine/iodide dose and tracked how much was excreted over the next 24 hours.

What they found was striking.

Among 116 patients with no known high iodine exposure, the median urinary iodine concentration was just 88.8 µg/L, which the World Health Organization defines as mild deficiency. In fact, over half the patients fell below the adequacy threshold of 100 µg/L. Serum iodine levels were also low, and in every single one of the 36 patients who completed the iodine loading test, less than 90% of the dose was excreted—suggesting that the body was holding on to iodine, indicating systemic need (Hartmann et al., 2025).

Even more telling were the findings on halide displacement. After the iodine challenge, patients excreted more fluoride and bromide than they did beforehand. This suggests that the new iodine was pushing those halides out—evidence, albeit indirect, of competitive inhibition at work. It supports the idea that fluoride and bromide may functionally increase iodine requirements in modern populations.

Why You Haven’t Heard About This

Mainstream iodine testing is rare. Medical guidelines don’t require it. National surveys still mostly rely on spot urine iodine concentrations, which fluctuate with hydration and don’t give reliable individual results. Even the iodine-loading test used in this study—where a high dose of iodine is administered to see how much is retained—is not officially endorsed by WHO, CDC, or endocrine societies.

And yet, that test tells a story. If the body keeps most of the iodine you give it, it probably needed it.

What this Florida study shows is a layered view: spot tests, serum iodine, challenge tests, and displacement patterns. This is a signal that calls for better measurement.

Read the rest here.