by Sharon Rondeau

(Dec. 27, 2023) — Continuing the work begun by the Voter Integrity Project, founded by Matt Braynard in late 2020, the non-profit Look Ahead America (LAA), also founded by Braynard, reported earlier this month a significant increase in instances it has discovered of questionable voting often gleaned from tips from the public.

A December 4, 2023 press release states that as of May, LAA had identified 134 cases of potential voter fraud based on research performed by volunteers using publicly-available tools; by the latter press release, that number had increased to 281, most of which stem from the 2020 general election.

The Post & Email learned of LAA’s work in the area of election integrity more than two years ago after receiving a press release about its work and objectives. Subsequently, we interviewed Director of Research Ian Camacho on several occasions regarding the group’s efforts to build Americans’ confidence in the nation’s elections by identifying potential instances of voter fraud spanning at least six different categories.

The organization’s May 10, 2023 press release revealed that of the then-132 cases open, a majority, 111, originated in Texas. As of that time, an LAA referral to officials in Tennessee and Florida had resulted in a conviction for double voting, while “a handful of cases not pursued but still prosecutable under the statute of limitations” remained, according to the press release.

Eight cases LAA referred for potential prosecution in various jurisdictions had been taken up by state officials, Camacho stated in the December 4 press release, adding, “We ask that the other states which have our cases open to examine the evidence and data in a timely manner instead of running out the clock on the statute of limitations, or worse, dismissing these complaints without review.”

States Involved

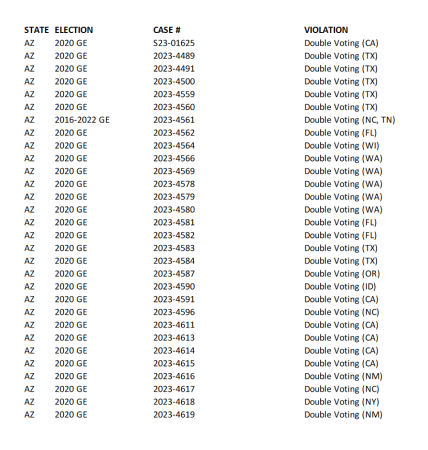

Linked to the press release is a ten-page roster of suspected cases of ballot fraud LAA submitted to officials in Texas, Arizona, Georgia, Wisconsin and Michigan bearing case numbers, which indicate acknowledgement of each complaint but not necessarily investigation or prosecution.

The names of those suspected of committing election fraud are redacted to protect the integrity of any investigations which might ensue, LAA wrote.

Scrutiny of the roster reveals the majority of the cases originated with suspected “double voting” in either Arizona or Texas, while the last seven, from Wisconsin, were identified as voters having apparently submitted a post office box or other impermissible address as a permanent residence in their voter registrations in violation of Wisconsin law.

“I followed up with some of them and don’t know what’s going to happen with them,” Camacho told us in an interview December 18, although at least two may see prosecution.

At times, he said, he suspects prosecutors decline to pursue a case because of political leanings. ”A lot of them I sent to the Texas Secretary of State, and in Arizona, they actually called me and said they weren’t going to do anything with it,” Camacho said. ”It is political in Arizona, because they’re going after the two people in Cochise County” (for allegedly “interfering with the 2022 election”), “so why not voter fraud?”

Camacho was referring to an LAA case in which a voter appeared to have voted in 2022 in both Arizona and Indiana for which he provided sworn testimony to the election board in the affected Indiana county.

In an update Wednesday, Camacho expressed confidence the case would be prosecuted as the result of a conversation he had with a local police detective. ”I went over all the statutes that applied as well as penalties both in terms of double voting and registration violations (a mix of felonies and misdemeanors) so it sounds like it will go in that direction,” Camacho told us in an email.

Other findings from the roster are labeled “OOSSR,” or “out-of-state subsequent registration,” indicating, Camacho said, that the voter cast a ballot in one state after having registered a permanent change of address and registered to vote in another state.

In regard to LAA’s research and referrals to election officials, Camacho told us human error or unknown variables can occasionally lead to false positives. “I can only tell them what I’m seeing,” he said.” I know my data is pretty good; it’s not perfect. I have a handful — less than ten — that have been dismissed as a mistake.”

“Debunked?”

In one instance, Camacho said, the organization American Oversight reported an LAA finding of potential voter fraud in Missouri “debunked,” but the claim was never supported by evidence. “I never heard anything back on this,” Camacho told us after he inquired of AO as to where it obtained its information. ”The article doesn’t provide any evidence it was ‘debunked.'”

American Oversight has characterized various reported findings of potential voting violations as comprising a “conspiracy-driven push for states to abandon [the] ERIC voter list program,” a reference to the Electronic Registration Information Center.

Is ERIC Cost-Effective…or Effective?

Founded in 2012 and designed to “help states improve the accuracy of America’s voter rolls, increase access to voter registration for all eligible citizens, reduce election costs, and increase efficiencies in elections,” ERIC currently shows 24 states and the District of Columbia as members.

The cost for a state to join the consortium is $25,000, the website states. “Members also pay annual dues,” it reveals, and”Dues for the 2023-24 fiscal year range from about $37,000 to about $174,000. ERIC’s 2023-24 operating budget is about $1,729,000.”

The organization produces four types of reports, it states, to assist members in updating their voter rolls relative to voters’ relocations in- or out-of-state, duplicate voter registrations and deaths.

According to NPR in October:

Nine states — all Republican-led — have now withdrawn from ERIC.

They all left without a plan to replace it.

And now, experts and election officials are watching a scattershot effort on the right to essentially recreate what the system produced, with many players — both mainstream and fringe — throwing their hats in the ring to try to capitalize on the data void.

According to the Foundation for Government Accountability (FGA), “more states should follow” those which canceled their ERIC membership earlier this year. ”To maintain up-to-date and accurate voter rolls, states should stop outsourcing voter roll maintenance efforts to politically driven, third-party groups like ERIC and instead follow the lead of other states that are using their own tools to achieve clean and accurate rolls,” the organization states in a December 13 post. Further, it claims, “ERIC was formed to help states maintain accurate voter rolls and spot illegal voting.3 But instances of duplicate voting and out-of-state or out-of-precinct voting continue despite ERIC’s involvement. ERIC has failed at its stated mission of maintaining voter rolls because its true mission is to increase voter registration. Fortunately, a growing number of states are leaving ERIC, and more should follow.4”

In a case involving a double voter in Texas and New Mexico which Camacho believes will be prosecuted imminently (page 7 of roster), he pointed out that ERIC either failed to flag the double registration or local officials, for whatever reason, did not act on the information. “What I wrote in my affidavit is that both Texas and New Mexico were ERIC-participating states,” Camacho said. In his affidavit, he recalled writing, “What is strange to me is that both Texas and New Mexico were ERIC-participating states. New Mexico joined in July of 2016, and Texas joined in 2020.”

“Texas left ERIC this year,” Camacho continued. ”It should have caught the double registration, let alone the double votes. The sheriff got to the case so late that 2020 was past the statute of limitations, but since the guy double-voted yet again in 2022, they got him for three more years and could use the double votes from 2014-2020 against him. So either ERIC failed to notify or if ERIC did notify, the secretary of state failed to notify the clerks, but somebody somewhere dropped the ball because this was the first time the sheriff and the clerks had heard about it. So I wondered, ‘How do you miss this?’ ERIC should have flagged the registration.”

In a March 2, 2023 statement, ERIC’s executive director, Shane Hamlin, wrote, in response to what he alleged was “recent misinformation spreading about ERIC”:

ERIC is a non-profit membership organization created by state election officials to help improve the accuracy of state voter rolls and register more eligible Americans to vote. This has been our mission since 2012.

We are a member-run, member-driven organization. State election officials – our members – govern ERIC and fund our day-to-day operations through payment of annual dues, which they set for themselves.

We analyze voter registration and motor vehicle department data, provided by our members through secure channels, along with official federal death data and change of address data, in order to provide our members with various reports. They use these reports to update their voter rolls, remove ineligible voters, investigate potential illegal voting, or provide voter registration information to individuals who may be eligible to vote.

ERIC is never connected to any state’s voter registration system. Members retain complete control over their voter rolls and they use the reports we provide in ways that comply with federal and state laws.

American Oversight characterizes those opposed to ERIC membership as “election deniers.” In a December 12, 2023 article subtitled, “How far-right misinformation and the election denial movement led nine states to reject the Electronic Registration Information Center,” invoking Camacho’s election-integrity efforts, AO wrote:

Information gleaned from VoteRef has fueled numerous voter challenges and fraud allegations. In February 2023, Ian Camacho — the research director at Look Ahead America, a group that supported defendants facing charges for participating in the January 6 insurrection [138] — contacted a Texas Senate staffer asking about the status of dozens of challenges submitted by an “anonymous tipster” known as Totes Legit Votes. [xlix] According to an email from the staffer to the Texas secretary of state’s office, the tipster had flagged “approximately 75” alleged double voters. [l] The secretary’s office responded that its Elections Division had received multiple emails from Totes Legit Votes, but that because of the high volume, the office was not sending acknowledgments in response to each message. [li]

Records of similar complaints lodged by Camacho and Totes Legit Votes with the Missouri secretary of state’s office in March suggest that they had used the VoteRef database. [lii] Camacho also cited VoteRef data in an email to election officials in Wake County, North Carolina, alleging instances of double voting. [liii] The records from Missouri indicate that officials quickly debunked several of the allegations, [liv] even cautioning staff not to click on links shared by Totes Legit Votes. [lv] Other documents reveal several requests from the Voter Reference Foundation for data from the Wyoming, West Virginia, and Rhode Island secretaries of state. [lvi]

The documentation AO presented in its corresponding footnote leads to a 724-page PDF, the first two pages of which show, in reverse order, a records request from AO to the Missouri secretary of state’s office under the “Sunshine Law” via an unrevealed attachment as well as the secretary of state’s response.

Pages 3-12 of the documentation AO received from the Missouri secretary of state comprise a “newsletter” published in August by the federal Election Assistance Commission (EAC) covering such topics as “National Poll Worker Recruitment Day,” “Recaps of the EAC Data Summit,” and “Latest EAC Resources,” among others.

Pages 13 and 14 consist of emails between Ohio secretary of state’s office employees; following that is communication from the West Virginia secretary of state’s office to a party whose name was redacted.

Using the “Find” feature in the PDF for the term “Camacho” yielded results between pages 63 and 162 containing Camacho’s emails to local Missouri election offices reporting an instance LAA had identified as a possible double voter.

The first such email is directed to “Nodaway County MO and Johnson County, TX Elections Divisions” reporting a “Potential Double voter in 2020 GE” (general election) in both jurisdictions.

Subsequently, Nodaway County Clerk Melinda Patton asked Missouri Director of Elections Chrissy Peters and her colleagues how to respond to Camacho’s proffering of the information.

On March 9, Peters responded to Patton:

Our office contacted Ian directly to discuss the complaint process with our office. He should be filing with us. We will contact you if we have any questions but we would typically work directly with the other state. Normally when we look into these situations we may need to request from you a signature from the poll book or absentee ballot envelope. We will let you know if we need to take next steps. Thank you!

The following day, Patton suggested to Peters that her office could have made an error by recording a ballot cast by the voter Camacho had questioned rather than by the individual who actually voted.

“Is this something that can be corrected? The election is closed, so I assume we cannot do it?” Patton asked Peters, followed by:

Additionally, how long are we looking to keep the November 2020 election stuff? Am I able to get rid of unvoted ballots to free up some space?

As always, thank you for your assistance in these matters.

In the course of his work he has been accused of presenting “only one side” of election-fraud claims, Camacho said, but “election integrity does not have a side, just as truth doesn’t take a side. It is what it is. There’s ‘election integrity’ vs. ‘You’re just trying to penalize the other side.’ I don’t choose the police, investigators or the DA who might go after it. That is out of my hands. I just submit the evidence and they determine it from there. I don’t have that power; I wish I did, but I don’t have legal authority. I’m just a concerned citizen submitting evidence; if they feel it warrants further investigation, they pursue it.”