by Joseph DeMaio, ©2023

(Jun. 29, 2023) — [See previous installments in this series here and here. The “CKA” article referred to below can be found here. Emer de Vattel’s “treatise” is “The Law of Nations,” also referenced earlier in the essay. – Ed.]

In reality, the notion that a child born anywhere in the world to British parents, who themselves were “subjects of the Crown,” became also a “subject of the crown” would constitute a useful template for determining whether a child born to U.S. citizen parents – members of a new constitutional republic and not a monarchy – anywhere in the world is counterintuitive. The United States had gone to war, and defeated the most powerful military empire in the world at that time, to among other things specifically cast off the then-existing “subject-liege” relationship, replacing it with a “citizen-republic” relationship. Stated otherwise, the Founders intended to restrict the presidency to a “natural born Citizen,” not a “natural born Subject.”

Furthermore, the CKA seeks to fortify the relevancy of its “British Subject” and “binding law in the colonies” position with a citation to “a text widely circulated and read by the Framers and routinely invoked in interpreting the Constitution…,” Blackstone’s Commentaries. The CKA cites pp. 354 – 363 of Blackstone’s treatise for its discussion of the nature and relationship between and among “persons,” which Blackstone subdivides into various categories, including “natural born subjects,” “aliens” and “denizens.”

Interestingly, Blackstone observes (at p. 362) that if an alien becomes naturalized by an act of Parliament, the alien “is put in exactly the same state as if he had been born in the king’s legiance [i.e., a “natural born subject”]; except only that he is incapable, as well as [is] a denizen, of being a member of the privy council, or parliament….” (Emphasis added) The Privy Council served as the body of most trusted advisors to the king or queen, and its membership was exclusive.

Of even greater interest as bearing upon the CKA’s claim that only one parent need be a U.S. citizen for the child to be a “natural born Citizen” under the Constitution – but somehow omitted, again likely inadvertently, from discussion in the CKA – Blackstone notes (at p. 224) regarding membership on the Privy Council:

“As to the qualifications of members to fit this board: any natural born subject of England is capable of being a member of the privy council; taking the proper oaths for security of the government, and the test for security of the church. But, in order to prevent any persons under foreign attachments from insinuating themselves into this important trust…, it is enacted by the Act of Settlement [Stat. 12 & 13 W. III. c. 2.], that no person born out of the dominions of the crown of England, unless born of English parents, even though naturalized by parliament, shall be capable of being of the privy council.” (Emphasis and bolding added)

The significance of Blackstone’s comment cannot be understated: he is articulating the point that, in order to prevent foreign influence in the Privy Council, if a “natural born” British subject seeking membership on the council was born “beyond sea” or otherwise “out of the dominions of the crown,” only if that person were born to “English parents,” in the plural, would he/she be eligible. One parent would not suffice: both (i.e., two, a mother and a father) needed to be English subjects.

This articulated concern – i.e., that as an additional barrier to the insinuation of “foreign influence” into the Privy Council, an office of “important trust,” only natural born British subjects born to “English parents” if born “beyond sea” would be so eligible – is conceptually indistinguishable from the Founders’ frequently-cited concern that all available barriers to the entry of foreign influence to the office of the president be interposed. A requirement that a “natural born Citizen” be the issue of two U.S. citizens at the time of birth constitutes a higher barrier than would the mere impediment of requiring only one of the child’s parents to be a U.S. citizen. Again, this is not rocket science.

As your humble servant has noted here, the implausible theory that the Founders favored a definition of “natural born Citizen” requiring only one citizen parent (or as the Congressional Research Service “theories” advocate, even zero U.S. citizen parents), is premised on the irrational conclusion that the Founders were intent on selecting a lower standard for the barrier on foreign influence in the presidency when a well-known and respected higher standard existed. That higher standard, of course, and one set out in § 212 of Emer de Vattel’s treatise, is that only if a child is born in a nation to two parents who at the time of birth are already citizens of that nation will the child be properly known as a “natural born citizen.”

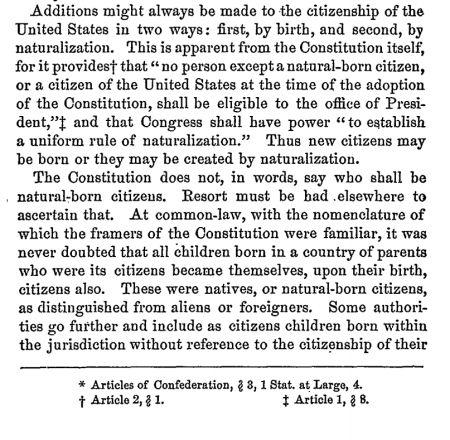

Indeed, this higher standard is the crux of the oft-quoted passage from the Supreme Court’s decision in Minor v. Happersett, 88 U.S. 162, 167-168 (1875). There, without specifically citing de Vattel, the Court stated:

“At common-law, with the nomenclature of which the framers of the Constitution were familiar, it was never doubted that all children born in a country of parents who were its citizens became themselves, upon their birth, citizens also. These were natives, or natural-born citizens, as distinguished from aliens or foreigners. Some authorities go further and include as citizens children born within the jurisdiction without reference to the citizenship of their parents. As to this class there have been doubts, but never as to the first.” (Emphasis and bolding added).

This language plainly demonstrates (a) that the Supreme Court believed that the “common law” precepts governing the “natural born citizen” issue turned on the fact that it was the citizenship of “the parents” – in the plural rather than the singular – that controlled and (b) that of the two theories supporting recognition of “natural born citizen” status – one requiring both parents to be citizens, the other disregarding parental citizenship – although the latter category was burdened with doubts, the first category had always been free of any such doubt. The CKA completely ignores these facts.

7. “1 Stat. 103 and the Term ‘Considered’”

After discussing Blackstone, the CKA then turns to the enactment by Congress in 1790 of 1 Stat. 103 and its provision that the children of U.S. citizen parents – in the plural – “shall be considered as natural born citizens.” The CKA states:

“The First Congress established that children born abroad to U.S. citizens were U.S. citizens at birth, and explicitly recognized that such children were ‘natural born citizens.’ The Naturalization Act of 1790 provided that ‘the children of citizens of the United States, that may be born beyond sea, or out of the limits of the United States, shall be considered as natural born citizens….’”

To begin with, the CKA assertion that in enacting 1 Stat. 103, Congress “explicitly recognized that such children were ‘natural born citizens’” is both linguistically and semantically misleading. The term “explicit” and its adverb variant “explicitly” mean “clearly and without any ambiguity.” (Emphasis added) The fact that Congress also conditioned the words used by stating such children were to be “considered” as nbC’s is linguistically and semantically not the same as stating that such children “are” or “were” nbC’s. Thus, the use of the term “considered” produces the ambiguity of describing them “as if” they were, in actuality, something that they were not.

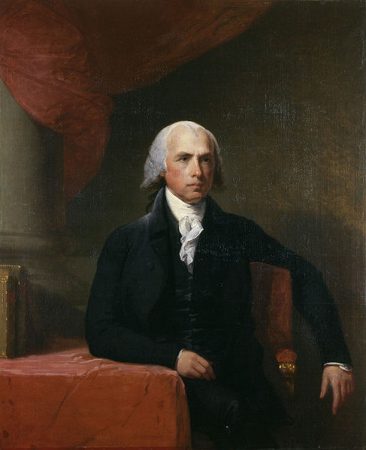

Accordingly, the claim that Congress was purportedly, without ambiguity or potential for misunderstanding, declaring such a child to be a “natural born citizen” for purposes other than the naturalization statute that 1 Stat. 103 in actuality was and is misleading and in error. Indeed, this may well have been one of the precipitating anomalies which led Founder James Madison and the Congress in 1795 to repeal altogether 1 Stat. 103, replacing it with 1 Stat. 414. That later statute, of course, deleted the “natural born” modifier before the word “citizens,” but retained the “considered as” language of the prior law.

The CKA also then asserts:

“The actions and understandings of the First Congress are particularly persuasive because so many of the Framers of the Constitution were also members of the First Congress. That is particularly true in this instance, as eight of the eleven members of the committee that proposed the natural born [Citizen] eligibility requirement to the Convention served in the First Congress and none objected to a definition of ‘natural born Citizen’ that included persons born abroad to citizen parents [citing, in footnote 10, “See Christina S. Lohman, Presidential Eligibility: The Meaning of the Natural-Born Citizen Clause, 36 Gonz. L. Rev. 349, 371 (2000/01).]” (Emphasis added)

At the outset, note that the CKA’s statement that “none objected to a definition of ‘natural born Citizen’ that included persons born abroad to citizen parents” is both a misstatement of fact as well as a non sequitur. 1 Stat. 103 did not supply a “definition” of natural born Citizen. Instead, it merely declared (unconstitutionally, it is submitted) that certain children born “beyond sea” were to be “considered” as such. That is not a “definition” but is a “classification” or “categorization” rather than a “definition.”

Second, the Lohman law review article cited by the CKA in footnote 10 concludes, as does the CKA, that a child born beyond the limits of the United States can be a natural born Citizen, but only if both “parents” are U.S. citizens. This undercuts the CKA thesis that only one parent need be a U.S. citizen, itself a counterintuitive conclusion in light of the later potential for competing claims of allegiance or citizenship by the “foreign” parent’s country. This issue continues to cloud the nbC eligibility of Sen. Ted Cruz, the main beneficiary of the 2015 CKA.

Moreover, although the Lohman law review article articulates the conclusion that, based on the original enactment of 1 Stat. 103, Congress had purportedly adopted a “broader” definition of “natural born Citizen,” that conclusion is suspect, for several reasons.

First, the repeal of the “natural born” modifier of 1 Stat. 103 by 1 Stat. 414 is acknowledged in the law review article as being potentially undertaken because Congress recognized that it had exceeded its powers under the Constitution – which are limited to legislating regarding “naturalization” – by altering the nbC definition of Art. 2, § 1, Cl. 5. The article concedes:

“While reasons for this omission are unknown [sic], one could certainly posit that the legislature [i.e., Congress] recognized a possible constitutional conflict and sought to correct it. Further, the omission of ‘natural-born’ makes the statute look more like one devolving citizenship by naturalization. Yet, because it is unknown why “natural-born” was omitted [sic], it is premature to conclude that Congress did not consider such children natural born. fn. 156. [“156. Even if Congress did not consider such children ‘natural-born,’ it cannot change the constitutional Framer’s conception of ‘natural-born.‘]” (Emphasis added)

Precisely: Congress “cannot change the constitutional Framer’s conception of ‘natural-born.’” And what exactly was the original conception? Your humble servant posits that the Founders’ original conception of the term was adopted from § 212 of the de Vattel treatise. The closest U.S. Supreme Court decision to have addressed and discussed the issue in the context of the Constitution’s Eligibility Clause – they only place in the document where the nbC term appears – is the decision in Minor v. Happersett. Alas, like the CKA, the law review article does not even mention the nbC statement from the Minor case, much less attempt to explain or distinguish it.

Furthermore, the Lohman review article’s claim that “it is unknown why ‘natural-born’ was omitted” is not exactly correct. Specifically, evidence apparently exists – P&E reader caveat: yet to be fully documented – that Founder James Madison recognized in 1795 the “considered as natural born citizens” linguistic error in 1 Stat. 103 and became one of the leading proponents of the legislation that ultimately repealed the ill-advised modifier, i.e., 1 Stat. 414.

That recognition is acknowledged in a legal memo published in Vol. 113 of the June 14, 1967 Congressional Record of the House proceedings at pp. 15875 through 15880. The specific reference to Madison’s discovery is found at p. 15877. There, the memo – authored by one Pinckney McElwee, a private attorney in Washington, D.C. – states that James Madison sought to correct the error in 1795. Additional research would need to be done in order to confirm the accuracy of the McElwee memo as to Madison. The quote in the Congressional Record is quite long, but revealing as to why Congress recognized its error and took steps to correct it, the claim that it is “unknown” why the repeal occurred aside. The quote states:

“Although it is not within the power of Congress to change or amend the Constitution by means of definitions of languages [i.e., words and phrases] used in the Constitution so as to mean something different than intended by the framers (amendments being governed by Article V) an argument might be advanced to the effect that the use of identical language by Congress substantially contemporaneously might be considered in later years by a court to reflect the same meaning of the same words by the framers of the Constitution; and under this argument to attach importance to the Act of Congress of March 26, 1790 (1 Stat. 103).

This argument fades away when it is found that this act used the term “natural-born” through inadvertence which resulted from the use of the English Naturalization Act (13 Geo. ITI, Cap 21 (1773)) as a pattern when it was deemed necessary (as stated by Van Dyne) to enact a similar law in the United States to extend citizenship to foreign-born children of American parents. In the discussion on the floor of the House of Representatives in respect to the proposed naturalization bill of a committee composed of Thomas Hartley of Pennsylvania, Thomas Tudor Tucker of South Carolina and Andrew Moore of Virginia, Mr. Edamus [Aedanus] Burke of South Carolina stated, ‘The case of the children of American parents born abroad ought to be provided for, as was done in the case of English parents in the 12th year of William III.” (See pp. 1121, Vol. 1 (Feb. 4, 1790) of Annals of Congress.) The proposed bill was then recommitted to the Committee of Hartley, Tucker and Moore, and a new bill the provision in respect to foreign-born children of American parentage was included, using the Anglican phrase “shall be considered as natural born citizens.” Manifestly, Mr. Burke had given the wrong reference to the Act of Parliament of the 12th year of William which was an inheritance law. But, it [i.e., 1 Stat. 103] was a naturalization bill and the reference to the English acts shows the origin of the inadvertent error in using the term natural-born citizen instead of plain ‘citizen’ came from copying the English Naturalization Act.

Mr. James Madison, who had been a member of the Constitutional Convention and had participated in the drafting of the terms of eligibility for the President, was a member of the Committee of the House, together with Samuel Dexter of Massachusetts and Thomas A. Carnes of Georgia when the matter of the uniform naturalization act was considered in 1795. Here the false inference which such language might suggest with regard to the President was noted, and the Committee sponsored a new naturalization bill which deleted the term ‘natural-born’ from the Act of 1795. (1 Stat. 414) The same error was never repeated in any subsequent naturalization act.” (Emphasis and bolding added)

While the CKA and Ms. Lohman – as well as the Congressional Research Service – may dispute the content of the McElwee memo, it can be accessed in the Congressional Record and anyone can review it and arrive at his own conclusions. Unsurprisingly, your humble servant finds it persuasive, and it certainly constitutes something more than an “unknown” reason for the repeal of the “natural born” modifier.

In addition, while the Lohman law review article acknowledges – without citing the McElwee memo in the Congressional Record – that 1 Stat. 414 could well have been a reaction by Congress to correct its prior error in 1 Stat. 103, the article completely avoids – as does the CKA – addressing the fact that in the Wong Kim Ark case, Justice Horace Gray totally misstates the facts and thus misleads everyone regarding the history of the two laws.

Specifically, he claims that, in 1795, the language of 1 Stat. 103 was “reenacted” by Congress “in the same words” with the “natural born” modifier of the word “citizens” purportedly preserved. As discussed here, that is absolutely incorrect. Congress did just the opposite, urged on, evidently, by Founder and Virginia signatory to the Constitution, James Madison.

In the ensuing 125 years between the rendering of the WKA flawed 1898 opinion and 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court has taken exactly zero steps to correct the error by way of a notice of “erratum” or other administrative order informing readers of the error. Move along…, nothing to see here. Interestingly, Justice Gray’s opinion does not even acknowledge that 1 Stat. 103 was repealed, instead characterizing 1 Stat. 414 as being merely a “reenactment” of the prior statute’s language.

No wonder a person reading WKA – including Senators voting for S.Res. 511, discussed, post – may have believed, erroneously, that the nbC language from 1 Stat. 103 had not only not been repealed, but had been reenacted. And yet the WKA decision continues to be cited for the “be-all-end-all” conclusion that a “citizen at/by birth” is “good enough” to constitute one a natural born Citizen for presidential eligibility purposes. Those who persist in relying on WKA for the claim that it “settles” the nbC issue are depressingly mistaken.

8. “The Proviso Has Remained Constant”

The CKA next contends:

“The proviso in the Naturalization Act of 1790 underscores that while the concept of ‘natural born Citizen’ has remained constant and plainly includes someone who is a citizen from birth by descent without the need to undergo naturalization proceedings, the details of which individuals born abroad to a citizen parent qualify as citizens from birth have changed.”

Here, the CKA wanders far afield. The only two “provisos” in 1 Stat. 103 related to the residency of fathers in the U.S. and the methods for admission to citizenship of previously proscribed individuals. Those provisos had nothing to do with the “considered as natural born citizens” language repealed (and not reenacted) by 1 Stat. 414.

On the other hand, if the CKA intends to “characterize” the “considered as natural born citizens” language as a “proviso,” the effort still falls short. The CKA statement that the concept “has remained constant and plainly includes someone who is a citizen from birth by descent without the need to undergo naturalization proceedings…,” is manifestly in error. To reiterate, Congress did not “in the same words” reenact the nbC “faux” proviso of 1 Stat. 103 when it repealed that language and enacted 1 Stat. 414.

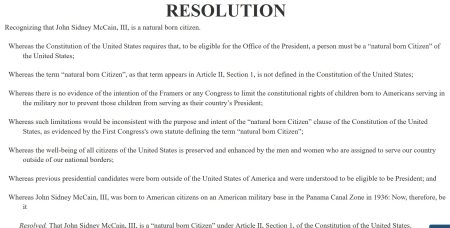

Indeed, the “ghost” of the repealed “natural born” modifier from 1 Stat. 103 also lies at the core of the meaningless expression of the U.S. Senate’s “sense” that Sen. John McCain was an eligible nbC when he ran for president in 2008. As discussed, post, the U.S. Senate, by unanimous consent, passed S.Res. 511 purporting to “ratify” the nbC presidential eligibility of then-Senator John McCain, despite his birth in Colón, Panama, albeit to U.S. citizen parents. The resolution was jointly moved through committee by, among others, Senators Hillary Clinton and Barack Hussein Obama, Jr. A cynic might be tempted to conclude that they had motivations other than assisting Senator McCain’s candidacy.

9. “Justice Story’s Commentaries”

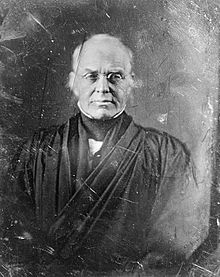

The CKA next cites Associate Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story and his famous treatise, “Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States,” first published in 1833. There, Justice Story confirms that:

“the purpose of the natural born Citizen clause was thus to “cut[] off all chances for ambitious foreigners, who might otherwise be intriguing for the office; and interpose[] a barrier against those corrupt interferences of foreign governments in executive elections.” (Emphasis added)

There is little if any disagreement over the fact that one of the primary concerns of the Founders was making sure, as much as possible, that the Constitution incorporated principles and language to preclude – not merely delay or impede – the insinuation in to the presidency of “foreign influence.” As Justice Story notes, the nbC clause was intended to cut off “all chances” for such a situation, not merely “some” or “a few” chances.

In this regard, the CKA reproduces the text of John Jay’s famous letter of July 25, 1787 to George Washington. In that letter, Jay “hinted” to Washington that it would be “wise and seasonable to provide a … strong check to the admission of Foreigners into the administration of our national Government; and to declare expressly that the Command in chief of the [A]merican army shall not be given to, nor devolve on, any but a natural born Citizen….” The CKA then cites (in footnote 13) § 1473 of Justice Story’s work for his keen observation that “the purpose of the natural born Citizen clause was thus to ‘cut[] off all chances for ambitious foreigners, who might otherwise be intriguing for the office; and interpose[] a barrier against those corrupt interferences of foreign governments in executive elections.’” (Emphasis added)

On the other hand, Justice Story’s observation, coupled with the language he uses, plainly underscores the reality that, in adding the nbC requirement to Art. 2, § 1, Cl. 5 of the newly-minted Constitution, the Founders’ intent was to altogether eliminate any chance that a chief executive with any foreign connections, whether by the soil (jus soli) or by blood (jus sanguinis), would be eligible to the presidency. Thus, it is clear that Justice Story was articulating an intent of the Founders which was not based on a goal of allowing “some” chance for ambitious foreigners to gain access to the office: the goal was to cut off all chances of that happening. The CKA “citizen at/by birth” model – allowing for “a” foreign parent or that parent’s native country to claim allegiance or citizenship in the child of the U.S. citizen “other” parent – produces just the opposite result.

Moreover, § 1473 of Justice Story’s work contains additional useful insight into the intent of the Founders with respect to the so-called “citizen-grandfather clause” inserted by the Committee on Postponed Matters into Art. 2, § 1, Cl. 5. That additional insight, found in the first four sentences of § 1473 – but, oddly, not included in the CKA commentary – will be offered here. The “citizen-grandfather clause,” of course, allowed as an exception to the “natural born Citizen” restriction on presidential eligibility, the eligibility of persons who held the status of a “Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution…,” whether native born or naturalized.

To reiterate, since none of the Founding Fathers would have been, in the Founders’ understanding under §212 of the de Vattel treatise, natural born Citizens, none would have been eligible to the presidency in the absence of the clause. To this point, Justice Story noted in the first five sentences of § 1473:

“It is indispensable, too, that the President should be a natural born citizen of the United States; or a citizen at the adoption of the constitution, and for fourteen years before his election. This permission of a naturalized citizen to become President is an exception from the great fundamental policy of all governments, to exclude foreign influence from their executive councils and duties. It was doubtless introduced (for it has now become by lapse of time merely nominal, and will soon become wholly extinct) out of respect to those distinguished revolutionary patriots, who were born in a foreign land, and yet had entitled themselves to high honours in their adopted country. A positive exclusion of them from the office would have been unjust to their merits, and painful to their sensibilities. But the general propriety of the exclusion of foreigners, in common cases, will scarcely be doubted by any sound statesman.” (Emphasis and bolding added)

Thereafter, Justice Story continues with the “ambitious foreigners” quote in the sixth sentence of the section. Thus, Justice Story reinforces the notion that even the Founders realized that there was a distinction between a “citizen” – whether denominated a “naturalized citizen” or a “native-born citizen” – and a “natural born Citizen.”

Again, were there no distinction between or among these differing classes of citizens, then there would have been no need for the citizen-grandfather clause at all. The fact that the clause may have had other benevolent purposes is immaterial: without it, none of the first seven presidents could have constitutionally served because none of them were nbC’s, at least under a §212 analysis. Furthermore, Justice Story’s observation that the intent of the Founders was to “cut off all chances for ambitious foreigners…” (emphasis added) to insinuate themselves into the office of the presidency simply cannot be squared with the theory that, instead, they intended only to cut off “some” chances or even “half of the chances” of such attempts by adopting an interpretation of the eligibility clause allowing but one or the other – but not both – of the parents of a child claiming nbC status to suffice.

10. “Jay’s Children Born Abroad”

The CKA concludes its observations on the role of John Jay and the purported continuing vitality of the concept – if not the repealed “letter” – of 1 Stat. 103, thusly:

“Indeed, John Jay’s own children were born abroad while he served on diplomatic assignments, and it would be absurd to conclude that Jay proposed to exclude his own children, as foreigners of dubious loyalty, from presidential eligibility [fn. 14 omitted].”

While CKA footnote 14 is omitted at the end of the above quote, its importance is now discussed. The footnote reference states: “See Michael Nelson, Constitutional Qualifications for President, 17 PRESIDENTIAL STUD. Q., 383, 396 (1987).” The citation to the Nelson article, presumably offered in direct support of the claim that “John Jay’s own children were born abroad while he served on diplomatic assignments,” raises troublesome questions.

The Nelson footnote, in turn, references (without a page citation) the Maryland Law Review article by Professor Charles Gordon, “Who Can Be President of the United States: The Unresolved Enigma.” A word-search of that law review article, however, reveals that the likely source of the speculation that Jay would not have favored a definition of “natural born” that disqualified his own children comes at pp. 7-8 of the Gordon law review article.

There, Professor Gordon states that the “Framers,” clearly including by inference John Jay, being familiar with the British rule that children born abroad to British natural born subjects where themselves British natural born subjects, “[t]here was no warrant for supposing that the Framers wished to deal less generously with their own children.”

But there is a potential problem here: bearing in mind that Internet sources, particularly “open source” (freely editable sites) may, or may not, accurately report empirical facts, the available record suggests that Jay and his wife, Sarah Livingston Jay, had six children, two boys and four girls. The Wikipedia pages for his sons Peter and William disclose that both of them were born in the United States, Peter on Jan. 24, 1776 in Elizabethtown, New Jersey and William on June 16, 1789 in New York City. Clearly, the sons were not born “beyond sea” and were, in fact, themselves nbC’s.

The birthplaces of Jay’s four daughters – Susan (born and died in 1780); Maria (b. 1782), Ann (b. 1783) and Sarah Louisa (b. 1792) – are not easily discovered for this offering, but if the CKA speculative statements about Jay are correct, the phrase “his own children, of dubious foreign loyalty” could refer only to Jay’s daughters, not his two sons. Moreover, even assuming that one or more of the daughters were born in France, Spain or elsewhere “beyond sea” while Jay was on diplomatic assignment, because he was beyond sea as a diplomat of the United States, retaining his U.S. citizenship status while abroad, so too would his daughters become U.S. citizens themselves when born. And as noted, Peter and William, of course, would have been otherwise eligible nbC’s without regard to 1 Stat. 103.

Finally, with regard to daughters Maria and Ann (Susan having passed away and Sarah Louisa being born after 1787), both of them would have been constitutionally eligible under the “citizen grandfather” clause of Art. 2, § 1, Cl. 5 as being U.S. “citizens” before May 29, 1790, the date of final ratification (Rhode Island) and formal “adoption” of the document.

This would be so even if it were to be shown that they were born abroad, since the “grandfather” exception clause requires only that the person be a “Citizen of the United States at the time of the Adoption of [the] Constitution,” without reference to birthplace. This may have been another oversight by the Founders, but it is now moot and academic as a result of the passage of time.

For these reasons, the CKA’s reliance on the Nelson article and its reliance, in turn, on the Gordon law review article for Jay’s “intent” regarding the nbC issue as expressed in his “hint” letter to George Washington is, at minimum, suspect.

11. “Senator Cruz as a ‘Citizen From Birth’”

Next, the CKA posits:

“Despite the happenstance of a birth across the border, there is no question that Senator Cruz has been a citizen from birth and is thus a ‘natural born Citizen’ within the meaning of the Constitution. Indeed, because his father had also been resident in the United States, Senator Cruz would have been a ‘natural born Citizen’ even under the Naturalization Act of 1790.”

Apart from trivializing the § 212 requirement for birth “in” the country with the term “happenstance,” the CKA’s use of the phrase “even under the Naturalization Act of 1790 (i.e., 1 Stat. 103) is misleading: it would be because of that law that Sen. Cruz could claim eligibility to being “considered” a natural born Citizen…, if that law had been in effect in 1970, when he was born. Memo to the authors of the CKA: in 1970, the “considered as natural born citizens” provision of the 1790 act had been dead – and perpetually buried – for 175 years.

12. “S. Res. 511”

The CKA next attempts to fortify its conclusions by referencing Senate Resolution 511, passed by the Senate in 2008 in purported support of Senator John McCain as he sought the 2008 GOP nomination for president. Because this offering is already too long, faithful P&E readers are directed here for an analysis of the resolution and why it was poorly reasoned. On the other hand, the CKA does make one assertion regarding S.Res. 511 necessitating comment.

The CKA states:

“Despite a few spurious suggestions to the contrary, there is no serious question that Senator McCain was fully eligible to serve as President, wholly apart from any murky debate about the precise sovereign status of the Panama Canal Zone at the time of Senator McCain’s birth. [fn. 17 omitted] Indeed, this aspect of Senator McCain’s candidacy was a source of bipartisan accord. The U.S. Senate unanimously agreed that Senator McCain was eligible for the presidency, resolving that any interpretation of the natural born citizenship clause as limited to those born within the United States was “inconsistent with the purpose and intent of the ‘natural born Citizen’ clause of the Constitution of the United States, as evidenced by the First Congress’s own statute defining the term ‘natural born Citizen.’ (Emphasis added)

There it is again: “spurious.” S.Res. 511 itself came closer than “a few suggestions to the contrary” to articulating a spurious theory of presidential eligibility. By claiming via one of its various “whereas” ipse dixit (“it is so because I say it’s so”) assertions that the ghost of 1 Stat. 103 had been resurrected to ratify John McCain’s nbC status, the resolution only ratified the fact that United States Senators do not need to pass constitutional law examinations.

And, by the way, quite apart from con law exams, while 1 Stat. 103 used the term “natural born Citizen,” plainly – at least to most English-speakers – it did not define it. To quote the Supreme Court’s opinion in Minor: “Resort must be had elsewhere to ascertain that.” It is posited that one “elsewhere” worthy of “resort” is § 212 of the de Vattel treatise, yet overlooked by the CKA.

The other thing worthy of comment in the CKA statement is the deployment of the neologism “natural born citizenship clause.” Nowhere in the Constitution or any Supreme Court opinion is Art. 2, § 1, Cl. 5 described as the “natural born citizenship clause.” General citizenship in the United States may be attained through birth or naturalization; but status as a “natural born Citizen” arises – it is posited under § 212 of de Vattel’s treatise, likely adopted by the Founders – only by birth here to a mother and a father who are already U.S. citizens. It is submitted that any attempt to dilute the § 212 definition by mischaracterizing it as the equivalent of general “citizenship” is, to borrow a term utilized by the CKA, also “spurious.”

13. “Specious Objections and a Refreshingly Clear Constitution”

The CKA concludes its analysis by stating:

“There are plenty of serious issues to debate in the upcoming presidential election cycle. The less time spent dealing with specious objections to candidate eligibility, the better. Fortunately, the Constitution is refreshingly clear on these eligibility issues.”

Once again, the CKA deploys, gratuitously, the pejorative “specious” to describe objections to a presidential candidate’s nbC status, as if to preempt any discussion at all – whether “specious” or “revealing” – bearing on the issue. The myriad anomalies and unanswered questions addressed in the foregoing offering cannot properly be deemed “specious” in the absence of “smoking gun proof” that the Founders – as opposed to well-credentialed and smart 21st Century lawyers – consciously intended to design and construct a pathway to the presidency for candidates imbued with foreign attachments. That potential lies at the heart of the “citizen at/by birth” theory espoused by the CKA. The unambiguous, “less-than-specious” record discloses that the Founders entertained no such objective.

As for the CKA’s assertion that “[f]ortunately, the Constitution is refreshingly clear on these eligibility issues…,” that claim is difficult to square with, as but one example, the title of Charles Gordon’s Maryland Law Review article, “Who Can Be President of the United States: The Unresolved Enigma,” cited with approval by the CKA. The unanswered question arises: how can the Constitution be “refreshingly clear” on the nbC issue and yet at the same time present an “unresolved enigma?”

As the Supreme Court noted in Minor v. Happersett, “[t]he Constitution does not, in words, say who shall be natural-born citizens. Resort must be had elsewhere to ascertain that.” Disregarding the Court’s observation that one must look “elsewhere” to ascertain who shall be a natural born citizen, the CKA claims to have uncovered the answer in the actual words of the “refreshingly clear” Constitution. One is tempted to ask: where, exactly, in the interstices of the Constitution’s “four corners” is it confirmed in “refreshingly clear” terms that the Founders intended a “citizen at/by birth” pathway to the presidency? Such a result might be well-received in a 2023 “wokeistan” country, but not in a 1797 United States of America.

At the end of the day, the simple question becomes this: presented with the § 212 “higher barrier to foreign influence” definition of a natural born Citizen, or the “lower barrier to foreign influence” inherent in the CKA-favored definition…, which one would the Founders more likely have adopted? I’ll wait.

Conclusion

Reasonable minds can and do differ, but they can disagree without being disagreeable. Respectfully, the foregoing, while in some ways perhaps somewhat “terse” or “snippy,” is not intended to anger or infuriate anyone, including Messrs. Clement and Katyal. But there remain legitimate, unanswered questions regarding what the Founders actually intended in adopting the “natural born Citizen” eligibility restriction. Direct evidence is sparse, necessitating reliance on more anecdotal or circumstantial evidence of intent. Your humble servant has his views…, and others have theirs. To its credit, at least the CKA avoids engaging in the disingenuous linguistic chicanery of the Congressional Research Service detailed here, here, here and here.

At bottom, a final resolution of the question will come only if one or the other of two events occurs: (1) the Supreme Court accepts a live, ripe “case or controversy” directly addressing the nbC issue and agrees to rule on it, either (a) reaffirming its WKA decision and the “citizen at/by birth” theory or (b) adopting the de Vattel § 212 nbC definition; or (2) a constitutional amendment is proposed and ratified either repealing and removing the nbC restriction altogether or clarifying which of the two competing nbC definitions to which the Republic will continue to adhere.

Full stop.

Was Barack H. Obama Sr., and Stanley Ann Dunham the same natural kind?

The Natural Born Citizen clause should never be removed it’s amazing how founders saw into the future and knew The USA would only survive if the President had allegiance to it. If we didn’t have the clause we would be back under Royal control.

We also know where we will be if we have the Natural Born Citizen clause, and ignore it…….