by ProfDave, ©2022

(Mar. 15, 2022) — 1278 years after the legendary founding of Rome, the British monk Dionysis Exiguus devised a dating system based on the conception [“incarnation”] of Jesus of Nazareth (± 4-6 years). Instead of using the brief reigns of earthly Kings and Consuls, years after the incarnation would be called “the year of our Lord” 1, 2, 525 etc. – Anno Domine, in Latin, or AD. Years before, came to be called “BC” or before Christ. There is no ‘0’ year or century. Thus Rome was founded 753 BC (8th century- counting backwards) and Dionysis did his thing in AD 525 (6th century). This system has become all but universal, even among those who do not believe in Christ. The writing of a “World History” would be just about impossible without it. Recent politically correct use of CE (“Common Era”) and BCE does not conceal the fact that the event that makes the era “common” is the alleged incarnation of Jehovah in the womb of Mary.

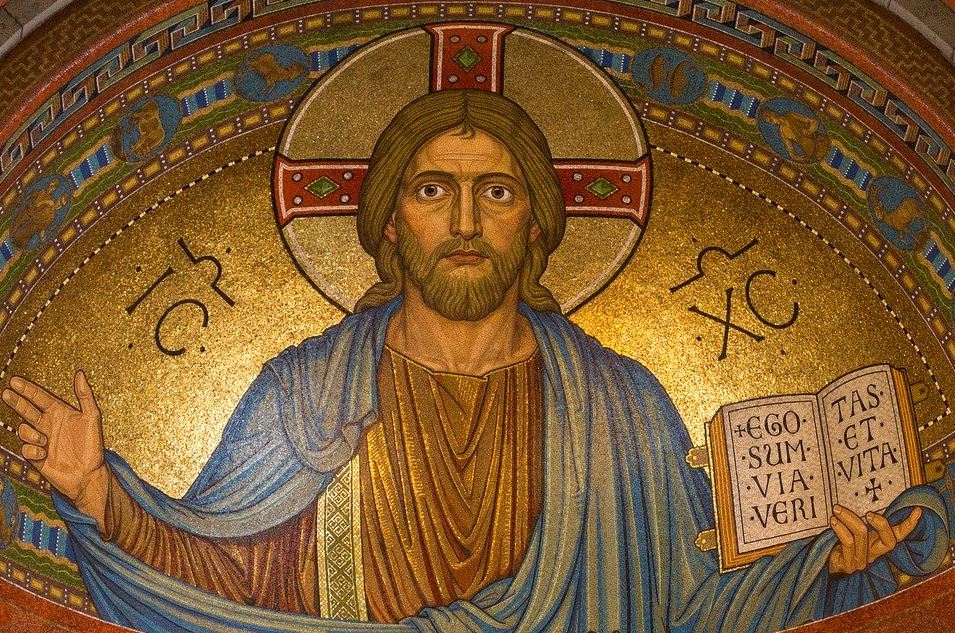

How did this extraordinary situation come to pass? How did a Galilean carpenter – who never wrote a book, held an office, or travelled outside Palestine (on the fringes of the Roman Empire), was deserted by his followers after only three years as a wandering Rabbi, then executed as a common criminal – make such a mark on the world? Remember, by Thucydides’ rules, we are limited to human and natural explanations: no appeal to the supernatural. If we do a conscientious job in examining the natural, the supernatural will become apparent. You can hardly expect a Christian like me to be entirely objective. On the other hand, I have spent a lot of time studying religious history. Let’s try.

Jesus began his teaching about 26 AD/CE, and Christianity, overcoming ferocious but sporadic opposition, became the dominant faith of the Roman Empire about 300 years later. Some of the major factors involved are the underlying power of the Hebrew spiritual heritage, the impact of a powerful conviction, the spiritual vacuum of the Greco-Roman world, the hope of eternal life, and the unity of the church.

First, Jewish people were, long before the time of Jesus, scattered throughout the known world. They may have constituted as much as 10% of the population in many provinces. They had won toleration and exemption from the requirements of the Roman civil religion – burning incense to the Spirit of Rome or Caesar and such. There was a synagogue in almost every urban center. Around these centers of Jewish faith and culture collected significant numbers of non-Jews who came to believe that the God of Israel was, in fact, the maker of heaven and earth. The ethical monotheism of the Jews represented a meaningful, yet down-to-earth synthesis of natural and supernatural, ethics and spirituality. Monotheism put both cosmology and ethics on a firm foundation.

At the same time, the situation in Palestine was a tinderbox. Many Jews did not appreciate the benefits of Roman rule but carried on a simmering insurgency. They looked back to the semi-miraculous liberation of their land from the Syrian Greeks by Judas Maccabaeus in 166 BCE (see the story of Hanukkah). Many looked for the fulfillment of prophecies of a coming Messiah (Anointed One – Christ in Greek) who would “save his people.” Calculations based on the prophet Daniel indicated the time was at hand. On the other hand, the Temple elites had come to an accommodation with the world as it was and feared the disruption and carnage of another rebellion. Three “Jewish Wars” followed in the next century, devastating large areas of the middle east, justify their concern.

Clearly, the teachings and allegedly miraculous activities of Jesus threatened this status quo. While outwardly observant, Jesus taught a brand of Judaism of the heart and an ethics that at once opened the door of “the Kingdom” to common sinners and would challenge the sincerity of the religious elite of any era or faith. But it was not for his ethics or his healings that he was executed, but for his claim to be the Messiah. The temple elite convicted him of blasphemy and turned him over to the Romans for execution as “the King of the Jews.” His disciples “forsook him and fled.”

Now things get really controversial. A great deal of ink and scholarship has been expended to show that nothing happened three days later, but most of the blood has been spilled to say something did. It has been suggested that Jesus never lived [too much evidence that he did], that he didn’t really die on the cross [again, too much evidence], and most of all, that he did not rise from the dead . Whatever happened, several hundred people, over the next forty days, were so absolutely convinced that they had seen him alive and well that they were cheerfully willing to lay down their own lives in testimony to it. And most of them did. So, at the end of the day, we have to try to explain their certainty. The oldest writings of Christianity clearly claim that this certainty – not the teachings or alleged miracles – was the inspiration of the church, and not the church the inspiration of the resurrection story.

The Greco-Roman world was particularly prepared to receive this message. The common Greek language, the Roman road system, and the network of Jewish synagogues with their Gentile fellow-travelers (“God-fearers”) all guaranteed that the story would reach from Spain and Britain to Ethiopia and India by the end of the first century. As a Jewish sect, it enjoyed Roman toleration until Gentile conversions and the Jewish Wars made bitter schism between Christians and unconvinced synagogue leaders. Christians began worshipping separately on Sunday, in celebration of the Resurrection, instead of on the Jewish Saturday – and were no longer protected by Roman toleration.

By the first century AD/CE, personal reliance on the traditional gods of Greece and Rome was mostly a matter of civic patriotism and formal observances. The intelligentsia looked for solace in philosophical worldviews, such as Stoicism and Epicurianism, but the general public found little comfort in either the brave acceptance of Fate or the bland and judicious avoidance of conflict. Neo-Platonism offered a metaphysical system that mirrored the hierarchical nature of Roman society. There were multiple levels of being, each a shadow of a higher ideal. Things were shadows of ideas which were shadows of gods which were shadows of an impersonal divine essence.

To supplement old fashioned polytheism and stale philosophy, there were the mystery religions, syncretic cults from Egypt and the East: Isis and Osiris, the Great Mother, Haddad of Damascus, Orphism, Mithras and (more or less orthodox) Zoroastrianism. They offered paths to personal salvation through multiple layers of secret initiation. They promised occult knowledge, elaborate rituals, and inner spiritual experiences.

Was Christianity another Eastern mystery cult? Well, it came from Judaism, and that was a different “East.” Other cults offered gods who died and were reborn in the spring, grieving mothers, personal salvation and immortality, but were not rooted in ancient writings and alleged concrete events. Nor were they associated with the high ethical standards of the Jews. At the same time, Christianity asserted the unity of Jew and Gentile, male and female, slave and free. These distinctive features may have given Christianity more cohesion and staying power than the esoteric cults.

The other thing Christianity had that the mystery cults mostly did not was persecution. Most of the early opposition was from other Jews who objected to the Christian outreach to non-Jews or from pagans who felt their idol-making business threatened. But when Christians were thrust out from under the Jewish umbrella, their creed, “Christ is Lord,” became a problem. Christians were free to believe as they pleased most of the time and in most matters. But the Roman Senate had taken to declaring the Imperator divine as a legal fiction to continue his orders after his death. As a token of loyalty, a pinch of incense was required as well as the pledge, “Caesar is Lord” – with divine implications. These formalities Jews, and now Christians, could not perform. Their ultimate allegiance was to Christ – above Caesar. This seemed unpatriotic. If the river flooded, or the crops failed, or the army was defeated, it was attributed to the lack of proper ceremonies. Omission became not just unpatriotic, but treasonous.

To refuse to acknowledge the gods of the Empire was to be an atheist and an enemy of mankind, while the refusal to yield to the Lordship of Caesar on the excuse of a higher authority was intolerable to Rome. Because they worshipped in secret and collected babies that had been put out with the trash, they were ignorantly accused of cannibalism, incest, and child sacrifice.

A systematic, universal, and long-term persecution applied in the first century might have suppressed the new faith, but by the time of Decius (4th century), it was too late. The saying goes, “the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church.” Bluntly, Christians died well – and, thanks to the Roman love of blood sports – very publicly. Taking the resurrection of Christ as a guarantee of their own, thousands found confidence to die rather than deny their faith. Threatening them with death did little good. Their courage was taken as convincing evidence of the truth of their claims. And positively, the hope of eternal life gave meaning to their lives and an impulse to benevolent action that paganism could not match. When life and the Empire was disintegrating, Christianity alone offered convincing hope.

One can well imagine that the necessity of secret worship and the constant threat of exposure would produce a disciplined and cohesive community. The early development of the Christian church is a little murky, but by the early second century, it had solidified around three authoritative features: local bishops, baptismal creeds (formal statements of doctrine recited by converts at initiation), and the writings of the apostles which later became the New Testament. These increased in power and universality over the next two centuries as bastions against persecution, and against fringe movements that sought to merge Christianity with sectarian Judaism (Ebionites), Greek philosophy, mystery religions (Gnosticism), and other offshoots. By the 4th century there was a strong unified hierarchical organization dependent on five apostolic centers: Rome, Jerusalem, Alexandria, Antioch, and Constantinople.These factors, and others, give us some understanding of the spread and growth of Christianity, despite its mostly underground status. By the time of toleration in 323, it commanded perhaps 30-40% of the population of the Empire and was also strong beyond the border in western Asia. Toleration brought a rush of mass conversions and a vast influx of wealth and power that changed forever both church and state, but the initial success of Christianity points to (in my biased opinion) an intrinsic spiritual superiority over its competitors.

Toleration finally came in 312. You could say it came down to a wager of battle. Constantine, fighting for the Imperial title, was camped outside Rome. His enemies had co-opted Jupiter, had the bigger army, and all the pagan auguries favored them. Constantine said he saw a sign in the sky, the monogram Chi Rho (X R), directing him to fight under the sign of Christ. He bet on Jesus and won the battle – spectacularly – and the crown. Whether or not that made him Christian is a matter of debate, but the church enjoyed Imperial favor during his reign and became the official Roman religion soon after. [Norman H. Baynes, “Constantine and the Christian Church,” Proceedings of the British Academy, vol XV (1929), 341-42]

Works consulted:

Africa, Thomas W., Sullivan, Richard E., and Sowards, J.K. Critical Issues in History.

Vol I. Boston: D.C. Heath, 1967.

Baynes, Norman H., “Constantine and the Christian Church,” Proceedings of the British

Academy, vol XV (1929), 341-42.

Klotsche, E. H. and Mueller, J. Theodore. The History of Christian Doctrine. Burlington,

IA: Lutheran Literary Board, 1945.

Noll, Mark A. Turning Points, 2nd Edn. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2000.

Rostovtzeff, M. Rome, Trans by J.D. Duff. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1960.

Scramuzza, Vincent & MacKendrick, Paul L.. The Ancient World. New York: Henry

Holt, 1958.

Sunshine, Glenn S. Why you think the way you do. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2009.

Spickard, Paul R. and Cragg, Kevin M. A Global History of Christians. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 1994.

Walker,Williston. A History of the Christian Church, 3rd edn. New York: Charles

Scribner’s Sons, 1970.

David W. Heughins (“ProfDave”) is Adjunct Professor of History at Nazarene Bible College. He holds a BA from Eastern Nazarene College and a PhD in history from the University of Minnesota. He is the author of Holiness in 12 Steps (2020). He is a Vietnam veteran and is retired, living with his daughter and three grandchildren in Connecticut.

Fascinating, although Jesus, as a youth, may well indeed have traveled far and wide with none other than Joseph of Arimathea. The latter thought to have been husband of Jesus’ great aunt was wealthy traveled through Roman world.. As closest male in family young Jesus would have been in his charge. These are oral traditions from the time of Christ and may shed light on his early years and travels. After the resurrection, Joseph presumed to have returned to what is now Britain, remarried, had descendants. Many British families with noble roots claim him as ancestor. The German tribe of the Frank’s is thought to have come to Christianity via a female descendent married to their king. These Frank’s were called Merovingians. The German family of President Trump comes from a village with fränkisch origins. In turn they claim descent from the most fearless of the Tribes of Israel, that of Benjamin whose warriors were trained to ambidextrous to confound their enemies.