INTRODUCTION AND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

by Joseph DeMaio, ©2015

(Mar. 23, 2015) — “The only principle to which most politicians will unfailingly adhere is expediency.” — Anonymous

Two recent events prompt this post. First, today, Senator Ted Cruz formally announced that he will be a candidate for the GOP nomination for president in 2016. The announcement was “scooped” here at The P&E by the intrepid and fearless editor of same. The second impetus for the post was that, earlier this month, two well-respected lawyers published a commentary in the Harvard Law Review Forum entitled “On the Meaning of ‘Natural Born Citizen.”

And so once again, ever-faithful P&E readers, the constitutional eligibility issue – like a humpback whale breaching the calm waters of the Pacific – boldly surfaces. Fair warning: for those interested in the “rest of the story” to follow, preparations should be undertaken for a lengthy and sometimes tedious analysis of the issue, for it is neither simple nor finally settled by the United States Supreme Court.

To begin with, there is, in this writer’s view, no doubt that Senator Cruz possesses the intellect, eloquence and strength of character to well and honorably serve the Nation as its president. From all appearances, he is closer to President Reagan (in this writer’s view, the “gold standard” of recent presidents) than any of the other reputed GOP candidates. Moreover, again in this writer’s view, Senator Cruz would be several light years ahead of and superior to the current president. However, for the same reasons articulated here at The P&E in the past with respect to the usurper now occupying the White House, Senator Cruz may well be ineligible to the office under the “natural born Citizen” clause of the U.S. Constitution.

And although the current usurper occupies the office only because (a) the U.S. Supreme Court continues to “evade” the presidential eligibility issue and (b) Congress lacks the courage to impeach him for the multitude of “high crimes and misdemeanors” he has committed apart from usurping, the fact remains that the Constitution and the interpretation of same should not be a function of the political party to which either a sitting president or an aspirant to the office belongs. Stated otherwise, the Founders were concerned with the integrity of the office and structure of the Nation: they were not concerned with political affiliations or expedient “go-along-to-get-along” results.

A few weeks prior to today’s announcement by Senator Cruz, there appeared in the March 2015 issue of the Harvard Law Review Forum,” the online companion to – but not to be confused with – that university’s “Harvard Law Review” journal the “commentary” to be discussed hereafter. “On the Meaning of ‘Natural Born Citizen’” is an article co-authored by two well-respected and distinguished law professors and practitioners, Mr. Paul Clement and Prof. Neal Katyal.

The article can be found at 128 Harvard Law Review Forum 161. As background, Mr. Paul Clement was appointed by President George W. Bush as the Solicitor General of the United States and served in that capacity between 2004 and 2008. Professor Neal Katyal is a former Acting Solicitor General of the United States, having replaced at the Office of the Solicitor General now-Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan. Both gentlemen now lecture at the Georgetown University Law Center and practice law in the Washington, D.C. area. Accordingly, both gentlemen are, shall we say, well-credentialed. That said, however, even well-credentialed persons occasionally can arrive at erroneous conclusions.

The gist of their commentary/article is that the “natural born Citizen” clause of the U.S. Constitution – Art. 2, Sec. 1, Cl. 5, mandating that only a natural born citizen is eligible to serve as president – should be interpreted to mean that anyone who is born to “a citizen parent…,” (emphasis added), whether the birth takes place here or anywhere else, is, to quote the commentary “… a U.S. citizen from birth and is fully eligible to serve as President [sic] if the people so choose.” See 128 Harv.L.Rev.F. at 164. In this regard, Messrs. Clement and Katyal specifically reference the potential candidacy of Senator Ted Cruz in the 2016 presidential election, and postulate that “… there is no question that Senator Cruz has been a citizen from birth and is thus [sic] a ‘natural born Citizen’ within the meaning of the Constitution.”

This presumably means that, in their view, even if one or the other of the parents is a foreigner or alien (i.e., not a U.S. citizen at the time of birth), but one or the other of the parents is a citizen, then the child is, at the time of the birth, a U.S. citizen and “thus,” in their opinion, a “natural born Citizen” within the meaning of the Constitution’s presidential eligibility clause as intended by the Founding Fathers. With due respect to these well-credentialed lawyers, there is a contrary argument.

Specifically, under some analyses which have delved more deeply into the interstices of the Founders’ intent when the natural born Citizen clause was inserted into the Constitution, and when viewed against the backdrop of the relatively few U.S. Supreme Court cases which have tangentially addressed the issue, the argument can be made that they intended that only a person born to two parents, both of whom were at the time of the birth already citizens of this nation, would meet the natural born Citizen criterion of the Constitution.

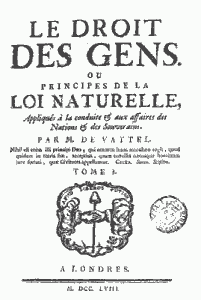

This interpretation is consistent with § 212 of Emmerich de Vattel’s “The Law of Nations,” a recognized treatise which the Founders frequently consulted in drafting the Constitution. More on that later in this post. The conclusion is also consistent with the rationales, if not the direct holdings, in several decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court, also discussed later.

This interpretation is consistent with § 212 of Emmerich de Vattel’s “The Law of Nations,” a recognized treatise which the Founders frequently consulted in drafting the Constitution. More on that later in this post. The conclusion is also consistent with the rationales, if not the direct holdings, in several decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court, also discussed later.

The Clement/Katyal Commentary (for the sake of brevity, hereinafter simply the “CKC”) has been immediately seized upon by various websites as purportedly confirming that Senator Cruz is constitutionally eligible. This conclusion is asserted despite the facts that (a) Senator Cruz was born in Alberta, Canada in 1970 and (b) at the time of his birth, although his mother, Eleanor E.D. Wilson, was a U.S citizen, his father, Rafael Cruz, was not a U.S. citizen, having been a Cuban citizen until 2005, when he became a naturalized U.S. citizen. And while the CKC posits that Rafael Cruz’s “residency” in the U.S. prior to 2005 sufficed to meet the “natural born Citizen” criterion, it fails to address or discuss the “two-citizen-parent” issue altogether.

Thus, the CKC reaches the same general conclusions as set forth in several “reports” and “memoranda” issued by the Library of Congress’s Congressional Research Service (“CRS”) and authored by one of its lawyers, one Jack Maskell, in 2009 and 2011. The conclusions reached by Mr. Maskell – along with a dissection of their conceptual deficiencies and grammatical shenanigans – have been addressed here at The P&E on several occasions by your humble servant, most notably here, here, and here.

And although the prior CRS products penned by Mr. Maskell sought unsuccessfully to shore up the purported constitutional eligibility of the current occupier of the White House, the CKC appears specifically to be intended to shore up arguments in support of the asserted constitutional eligibility of Senator Cruz. Moreover, while the CKC does not specifically cite in support of its conclusions either of the referenced CRS “Maskell” documents, with due respect, the CKC reads like a “CliffsNotes” version of them.

Accordingly, the question becomes: what is more important, principle or political expediency? Despite the CKC’s dismissive observation that “[t]he less time spent dealing with specious objections to candidate eligibility, the better…” (CKC, 128 Harv.L.Rev.F. at 164) and its extraordinarily curious claim that “[f]ortunately, the Constitution is refreshingly clear on these eligibility issues…” (id.), the questions surrounding whether the current occupant of the office or another aspirant to the office is constitutionally eligible as a “natural born Citizen” are neither “specious” nor are the answers “refreshingly clear.”

To the contrary, were the answers to these questions so “refreshingly clear,” there would no longer be any need for periodic commentaries and articles such as the CKC, particularly on the eve of another general election cycle, were at least one of the potential candidates for president to have the same sort of “eligibility” issues which have plagued the current occupant of the office.

Instead, unless and until the U.S. Supreme Court directly addresses the issue – one which it seemingly has been intent on “evading” since 2008 – the issues will persist, no matter how much they may be marginalized, trivialized and lampooned by the left, by the mainstream media, by the CRS and even by well-credentialed law professors. And if one were to channel Jay, Madison, Hamilton and Jefferson, a pretty good argument could be made that those Founders would agree.

Finally, to remove any lingering doubt as to this writer’s position, let it be known that it is his firm belief that the present occupant of the Oval Office is a usurper of the position. He is not now, nor has he ever been, nor will he ever be in the future a natural born Citizen as contemplated and intended by the Founders – even if ultimately actually proven (we are still waiting) to in reality have been born in Hawaii – because his father was never a U.S. citizen and remained a citizen of Kenya for his entire life. For that reason alone he should never have been elected or sworn into office by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Accordingly, he should be impeached and removed from office.

However, as stated above, although Senator Cruz possesses the intellect, eloquence and strength of character to well and honorably serve the Nation as its president, Senator Cruz may no more be eligible to occupy the office than is the current occupant. And if a contrary determination is to be made, let it come before November 2016 in binding, public form from a majority of the United States Supreme Court rather than from some well-credentialed law professors or from a lawyer employed by the CRS. It is, after all, only the structural integrity of the Nation that is at stake.

However, as stated above, although Senator Cruz possesses the intellect, eloquence and strength of character to well and honorably serve the Nation as its president, Senator Cruz may no more be eligible to occupy the office than is the current occupant. And if a contrary determination is to be made, let it come before November 2016 in binding, public form from a majority of the United States Supreme Court rather than from some well-credentialed law professors or from a lawyer employed by the CRS. It is, after all, only the structural integrity of the Nation that is at stake.

Interested? Curiosity piqued? Read on.

PRELIMINARIES

To begin with, in order to get a “full picture” of what is going on here, readers should first examine carefully the CKC. Second, readers should re-familiarize themselves (or initially do so, if they be newcomers to The P&E) on the topic with a few articles in the series of essays posted here addressing the deficiencies and “anomalies” of three major “products” of Mr. Maskell at the Congressional Research Service. Those articles are linked in the prior section of this post. Third, readers should keep handy a tutorial on these issues authored by one Stephen Tonchen and entitled “Presidential Eligibility Tutorial.” Finally, readers should keep a cup of hot coffee or other caffeinated beverage nearby – with plenty in reserve – because what follows may tend to be, let us say politely, tedious and convoluted. Ready? Let us proceed.

THE CLEMENT/KATYAL COMMENTARY AND 1 STAT. 103

As already noted, the thrust of the CKC is that, according to the authors’ analysis, “… the relevant materials clearly indicate that a ‘natural born Citizen’ [the capitalization of the “C” denoting the identification of the term in Art. 2, Sec. 1, Cl. 5 of the Constitution] means a citizen from birth with no need to go through naturalization proceedings.” (CKC, 128 Harv.L.Rev.F. at 161.) This is the essence as well of the CRS documents prepared by Mr. Maskell analyzed elsewhere.

Under decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court, notably United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898), following passage of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, the law has been that any person “born” in the United States, even to parents who are aliens and not citizens of the United States at the time of the birth, are themselves “citizens.” The usual nomenclature for such individuals is “native born citizen.” For future reference, the important thing to remember in this regard is that while all “natural born citizens” are also “native born citizens,” not all “native born citizens” are “natural born citizens.” Stated otherwise, “natural born citizens” constitute a smaller subset within the larger population of “native born citizens.”

The CKC cites the decision in Wong Kim Ark, but only for the proposition that, under the British common law and statutes which were “binding law in the [C]olonies before the Revolutionary War…” (CKC, id., at 162), the Founders were presumably familiar with the concept that “children born outside of the British Empire to subjects of the Crown were subjects themselves and explicitly used ‘natural born’ to encompass such children.” The CKC citation in support of that assertion is to pp. 655 through 672 of the Supreme Court’s Wong Kim Ark opinion.

The CKC cites the decision in Wong Kim Ark, but only for the proposition that, under the British common law and statutes which were “binding law in the [C]olonies before the Revolutionary War…” (CKC, id., at 162), the Founders were presumably familiar with the concept that “children born outside of the British Empire to subjects of the Crown were subjects themselves and explicitly used ‘natural born’ to encompass such children.” The CKC citation in support of that assertion is to pp. 655 through 672 of the Supreme Court’s Wong Kim Ark opinion.

The issue in that case involved the question of whether a person born in the United States to two alien (Chinese) parents was a “citizen by birth” under the Fourteenth Amendment. The issue presented was not whether Wong Kim Ark qualified as a “natural born Citizen” under Art. 2, Sec. 1, Cl. 5 of the Constitution, the eligibility clause. Accordingly, all of the Court’s lengthy discussion of the history of British common law preceding and contemporaneous to the drafting of the U.S. Constitution, and upon which the CKC relies, is dictum.

The Court, in a 6-2-1 (recusal) “split” decision, with Chief Justice Fuller and Associate Justice Harlan dissenting, a majority of the Court confirmed the native-born citizen status of Wong Kim Ark. The case did not, as many proponents of an expansive definition of “natural born Citizen” would erroneously argue, adjudicate who was, and who was not, eligible to serve as president under the Constitution. The case involved only Wong Kim Ark’s status as a native-born citizen.

Disregarding for the moment the fact that many legal scholars (and even the dissenting Chief Justice and Associate Justice John Harlan) contend that Wong Kim Ark was wrongly decided, the CKC makes no mention of the fact that the Court’s lengthy discussion of the British common law in the case was not part of the binding holding of the case, but instead was simple dicta.

Respectfully, analyses of what the Founders intended through the use of the term “natural born Citizen” in the Constitution should be based on more than obiter dictum. For this reason, the only anecdotal reference in the decision (169 U.S. at 671) to a 1677 British statute which intimated that “natural born subject” status of persons depended on the natural-born subject status of the father “or” the mother cannot be seen as persuasive.

Indeed, immediately following the Court’s discussion of that 1677 statute, the Court cited two other British statutes from 1708 (7 Anne (1708) c. 5, § 3,) and 1731 (4 Geo. II. (1731) c. 21) explaining that the law was intended to be limited to persons “…whose fathers were or shall be natural-born subjects of the crown of England, or of Great Britain, at the time of the birth of such children respectively,…” (Emphasis added). This principle, of course, mirrors that of § 212 of The Law of Nations. There, de Vattel posits that “… in order to be of the country, it is necessary that the person be born of a father who is a citizen; for, if he is born there of a foreigner, it will be only the place of his birth, and not his country.” (Emphasis added).

The CKC then posits that, because the First Congress was composed of many members of the original Constitutional Convention when the “natural born Citizen” requirement was added, its enactment of the first federal naturalization statute – the Naturalization Act of 1790 (1 Stat. 103) – is properly read in the same context of the British common law and British statutes with which the Founders, purportedly, were “intimately familiar… since the statutes were binding law in the [C]olonies before the Revolutionary War.” CKC, 128 Harv.L.Rev.F. at 162.

Quite apart from the questionable logic of the supposition that, simply because British statutes were “binding law in the [C]olonies” prior to the Revolutionary War, the Founders were content to bind themselves to their construction into the future and in the Constitution, the language of 1 Stat. 103 seems clearly to contemplate that the term “natural born citizens” as used therein is conditioned upon the birth of children “beyond the sea, or out of the limits of the United States,” only if born to “citizens of the United States.” It is absurd to posit, for example, that a lesser criterion of parental citizenship should be applied to children born to parents within the territorial boundaries of the United States as opposed to such births beyond such boundaries.

Had the First Congress intended either that (a) neither of such a child’s parents needed to be a citizen at the time of the birth – the nonsensical conclusion that the two major “Maskell” CRS documents postulate with regard to the current resident of the White House –, or (b) only one of the child’s parents needed to be a citizen at the time of birth, it would not have worded the statute as it did.

Had the First Congress intended either that (a) neither of such a child’s parents needed to be a citizen at the time of the birth – the nonsensical conclusion that the two major “Maskell” CRS documents postulate with regard to the current resident of the White House –, or (b) only one of the child’s parents needed to be a citizen at the time of birth, it would not have worded the statute as it did.

Throughout the CKC, the authors assert, via ipse dixit (i.e., “it is so because I say it is so”), that, against the backdrop of British common law, the Founders intended that a person born to “a citizen parent…” (including such persons as, for example, Senator Cruz) would meet the “natural born Citizen” criterion of the Constitution. However, several inconvenient facts and principles of common English grammar confirm that the CKC supposition is unfounded and likely incorrect.

First, as is true for any legislating body, it is presumed that members of the First Congress – including eight of the members of the Committee of Eleven, the subcommittee of the Committee of Detail at the Constitutional Convention and the one which submitted the “natural born Citizen” requirement to the full convention – knew the difference between the singular term “a citizen” and the plural term “citizens.” Indeed, the statute used both the singular and the plural of the word “citizen” throughout, but to mean different things. When it used the term “citizens,” it was thus connoting the plural of the word, not the singular.

Second, even in 1790, it was a biological fact that children could be “born” only through gestation and delivery by the mother. While the father unquestionably had a major role in events leading up to the “birth” of the child, the mother alone “gives birth,” but the child is born to both the mother and the father, who then become the child’s “parents.” Although the mother, as an individual, is one parent in the singular, and the father, as an individual, is the other parent in the singular, the two become, in the plural, the “parents.”

Similarly, the correct grammatical interpretation of the word “citizens” in the third full sentence of 1 Stat. 103 – stating that “… the children of citizens of the United States, that may be born beyond sea, or out of the limits of the United States, shall be considered as natural born citizens … [followed by two unrelated provisos]” – must be seen as referring to the plural of a mother and a father, i.e., two parents. Had the Congress intended in 1 Stat. 103 to extend natural born citizen status to a child born “beyond the sea or out of the limits of the United States” where only the mother was a citizen, it could have so stated.

Again, since only the “mother” in the singular can give birth, plainly, the selection of the plural term “citizens” with reference to the parents of the child can only be seen as an intentional action by the First Congress to limit status as a natural born citizen under the statute to those children born to “citizens of the United States,” in the plural, who were already citizens at the time of the birth rather than at some later date.

Stated otherwise, the reliance on anecdotal sources which suggest that but one parent of a child need be a citizen at the time of birth, whether the mother or the father, cannot with intellectual candor be reconciled with the universally recognized intent of the Founders that all barriers to the potential for foreigners to lay claim to presidential eligibility was to be the criterion. “All” barriers does not mean “some” barriers or “50%” of the barriers. It means “all” barriers, including that barrier which would require both parents of the child laying claim to being a “natural born Citizen” to be citizens at the time of birth, and not at some later date, if at all.

Third, and of greater significance, in a law review article cited and relied upon by the CKC in support of its conclusions (see CKC, 128 Harv.L.Rev.F. at 162, n. 10, citing Lohman, Presidential Eligibility: The Meaning of the Natural-Born Citizen Clause, 36 Gonzaga L.Rev. 349, 371.(2000/01), the author of the scholarly article specifically states with regard to the meaning of “natural born citizen” that “… the common law, at least with regard to foreign-born children, appears to contemplate only children of two citizen parents.” (Emphasis added). See Lohman, Presidential Eligibility: The Meaning of the Natural-Born Citizen Clause, 36 Gonzaga L. Rev. 349, 368 (2000/01). This is the thrust of 1 Stat. 103.

Moreover, throughout the law review article, the author consistently refers to “natural born citizen” children with an immediate coupling of the term to the plural terms “citizen parents” or “American citizens.” Unlike the CKC, nowhere in the Gonzaga Law Review article does the author even suggest, much less claim, that the Founders intended anything less than two U.S. citizen parents being required at the time of birth to constitute the sine qua non of the foreign-born child of U.S. citizen parents as being recognized as a “natural born Citizen.” See, e.g., id. at 368, 369, 371, 372, 373.

In reality, the law review article actually undercuts the CKC conclusion that the British common law, even if understood by the Founders, was invariably followed and adopted by them when drafting the Constitution, including the “natural born Citizen” eligibility requirement. Specifically, in analyzing the language of 1 Stat. 103 – the Naturalization Act of 1790 – the law review author states, 38 Gonz.L.Rev. at 371-372: “The 1790 act supports the proposition that the Framers did not strictly follow the English common law with regard to birthright citizenship, but rather followed the rule of jus sanguinis – or citizenship by descent…. The 1790 act passed by the First Congress is about as close as one can get to knowing whether the Framers considered foreign-born children of citizen parents to be ‘natural born.’” (Emphasis added).

Accordingly, the CKC’s conclusion that one’s status as a “natural born Citizen” is a function of whether only one, rather than both, of the parents is a citizen of the United States at the time of the birth is, with due respect, something less than “refreshingly clear.”

THE RELIANCE ON BLACKSTONE’S COMMENTARIES

The CKC also relies on an important legal treatise which was a source of reference by the Founders, that treatise being “Blackstone’s Commentaries.” The CKC notes that the British statutes in force in the Colonies before the Revolutionary War were “well documented” in that treatise, citing “1 William Blackstone, Commentaries *354-63.” Curiously, those pages of Blackstone’s “Commentaries on the Laws of England” address and discuss “fines” in the context of real property and what today would be called a “quiet title action.” Thus, the relevance of the citation in the CKC to the question of what constitutes a “natural born Citizen” is somewhat obscure.

There are, however, some passages from Blackstone’s Commentaries which do, in fact, shed helpful additional light on the topic. For example, where Blackstone addresses those “natural born subjects” who may be eligible to sit as members of the Privy Council – said council being a formal body of senior advisers to the sovereign in England – he notes (id. at 230): “As to qualifications of members to sit at this board: any natural-born subject of England is capable of being a member of the privy council, taking the proper oaths for security of the government, and the test for security of the church. [footnote omitted]. But, in order to prevent any person under foreign attachments from insinuating themselves into this important trust, as happened in the reign of king William in many instances, it is enacted by the act of settlement, [footnote omitted] that no person born out of the dominions of the crown of England, unless born of English parents, even though naturalized by parliament, shall be capable of being of the privy council.” (Emphasis added).

This articulated concern, i.e., that as an additional barrier to the entrance of “foreigners” into an office of “important trust,” only natural born British subjects born to “English parents” if born “beyond sea” would be so eligible, is conceptually indistinguishable from the Founders’ frequently-cited concern that all barriers to the entry of foreign influence to the office of the president be interposed. A requirement that a “natural born Citizen” be the issue of two U.S. citizens at the time of birth constitutes a higher barrier than would the mere impediment of requiring only one of the child’s parents to be a U.S. citizen.

As noted here, the implausible theory that the Founders favored a definition of “natural born Citizen” requiring only one citizen parent (or as the “Maskell theories” advocate, even zero citizen parents), is premised on the irrational conclusion that the Founders were intent on selecting a lower standard for the barrier on foreign influence in the presidency when a well-known and respected higher standard existed. That higher standard, of course, and one set out in § 212 of Emmerich de Vattel’s “Law of Nations,” is that only if a child is born in a nation to two parents who at the time of birth are already citizens of that nation will the child be properly known as a “natural born citizen.”

Indeed, this higher standard is the crux of the oft-quoted passage from the Supreme Court in Minor v. Happersett, 88 U.S. 162, 167-168 (1875). There, the Court stated: “At common-law, with the nomenclature of which the framers of the Constitution were familiar, it was never doubted that all children born in a country of parents who were its citizens became themselves, upon their birth, citizens also. These were natives, or natural-born citizens, as distinguished from aliens or foreigners. Some authorities go further and include as citizens children born within the jurisdiction without reference to the citizenship of their parents. As to this class there have been doubts, but never as to the first.” (Emphasis added).

This language plainly demonstrates (a) that the Supreme Court believed that the “common law” precepts governing the “natural born citizen” issue turned on the fact that it was the citizenship of “the parents” – in the plural rather than the singular – that controlled and (b) that of the two theories supporting recognition of “natural born citizen” status – one requiring both parents to be citizens, the other disregarding parental citizenship – although the latter category was burdened with doubts, the first category was free of such doubt.

To reiterate, therefore, if faced with the choice of constructing a “barrier” to foreign influence in the office by requiring “two-citizen parents” at birth, or erecting a merely lower “impediment” or “hurdle” which might be more easily cleared, which standard would have made more sense to the Founders? Rocket science this is not.

To reiterate, therefore, if faced with the choice of constructing a “barrier” to foreign influence in the office by requiring “two-citizen parents” at birth, or erecting a merely lower “impediment” or “hurdle” which might be more easily cleared, which standard would have made more sense to the Founders? Rocket science this is not.

Thus, it is clear that even William Blackstone, as well as the government of England, recognized that in order to prevent anyone with “foreign attachments” from “insinuating themselves into this [office of] important trust,” no “natural born subject,” even if otherwise eligible and born out of the dominions of England, and further even if naturalized by Parliament, would be eligible to sit as a member of the Privy Council “… unless born of English parents.” (Emphasis added).

The significance of this acknowledgment, of course, is that even England recognized, as to the Privy Council – an office of “important trust” – that a natural born subject who may have been born beyond sea or otherwise “out of the dominions of the crown of England” was eligible to the Privy Council only if born to “English parents.” (Emphasis added). Just as Blackstone speaks of the eligibility of such persons in terms of the plural term “parents,” so too does 1 Stat. 103 speak of offspring who are to be deemed “natural born citizens” in terms of those persons being “the children of citizens of the United States,” also in the plural.

In reaching a contrary conclusion – conveniently-timed to closely coincide with the announcement by Senator Cruz of his presidential candidacy – the CKC may not constitute the “last word” on the topic, nor, with respect, even the “correct” word.

THE RELIANCE ON JUSTICE STORY’S COMMENTARIES

In addition to reliance on Blackstone, the CKC cites and relies upon the work of U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Joseph Story in his famous “Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States” first published in 1833. In this regard, the CKC first notes (128 Harv.L.Rev.F. at 163) the text of John Jay’s famous letter of July 5, 1787 to George Washington. In that letter, Jay “hinted” to Washington that it would be “wise and seasonable to provide a … strong check to the admission of Foreigners into the administration of our national Government; and to declare expressly that the Command in chief of the [A]merican army shall not be given to, nor devolve on, any but a natural born Citizen….”

The CKC then cites § 1473 of Justice Story’s work (idem.) for his keen observation that “the purpose of the natural born Citizen clause was thus to ‘cut[] off all chances for ambitious foreigners, who might otherwise be intriguing for the office; and interpose[] a barrier against those corrupt interferences of foreign governments in executive elections.’” (Emphasis added). Parenthetically, there is no suggestion that Justice Story was clairvoyant in his observations in 1833 with respect to the recent efforts of the regime now in charge to undermine – apparently with U.S. taxpayer dollars – the March 2015 re-election of Benjamin Netanyahu as Prime Minister of Israel. If one seeks an example of “interference” in that election, one need look no farther than here.

On the other hand, Justice Story’s observation, coupled with the language he uses, plainly underscores the reality that, in adding the “natural born Citizen” requirement to Art. 2, Sec. 1, Cl. 5 of the newly-minted Constitution, the Founders’ intent was to “cut off all chances…” that a chief executive with any foreign connections, whether by the soil (jus soli) or by blood (jus sanguinis), would be eligible to the presidency. Thus, it is clear that Justice Story was articulating an intent of the Founders which was not based on a goal of allowing “some” chance for ambitious foreigners to gain access to the office: the goal was to “cut off all chances…” of that happening.

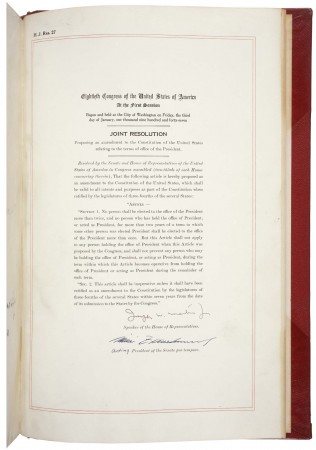

Moreover, § 1473 of Justice Story’s work, cited with approval by the CKC, contains additional useful insight into the intent of the Founders with respect to the so-called “grandfather clause” in Art. 2. Sec. 1, Cl. 5 of the Constitution. That additional insight, found in the first four sentences of § 1473, but not included in the CKC commentary, will be offered here. The “grandfather clause,” of course, allowed as an exception to the “natural born Citizen” restriction on presidential eligibility, the eligibility of persons who were a “Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution….” Since none of the Founding fathers were, in the Founders’ understanding, natural born Citizens, none would have been eligible to the presidency in the absence of the clause.

Indeed, to this point, Justice Story noted in the first five sentences of § 1473: “It is indispensable, too, that the president should be a natural born citizen of the United States; or a citizen at the adoption of the constitution, and for fourteen years before his election. This permission of a naturalized citizen to become president is an exception from the great fundamental policy of all governments, to exclude foreign influence from their executive councils and duties. It was doubtless introduced (for it has now become by lapse of time merely nominal, and will soon become wholly extinct) out of respect to those distinguished revolutionary patriots, who were born in a foreign land, and yet had entitled themselves to high honours in their adopted country. A positive exclusion of them from the office would have been unjust to their merits, and painful to their sensibilities. But the general propriety of the exclusion of foreigners, in common cases, will scarcely be doubted by any sound statesman.” (Emphasis added).

Thereafter, Justice Story continues with the “ambitious foreigners” quote in the sixth sentence of the section, the complete text of which reads: “It cuts off all chances for ambitious foreigners, who might otherwise be intriguing for the office; and interposes a barrier against those corrupt interferences of foreign governments in executive elections, which have inflicted the most serious evils upon the elective monarchies of Europe.”

Thus, Justice Story reinforces the notion that even the Founders realized that there was a distinction between a “citizen” – whether denominated a “naturalized citizen” or a “native born citizen” – and a “natural born Citizen.” Were there no distinction between or among these citizens, then there would have been no need for the “grandfather clause” at all.

Furthermore, to reiterate, Justice Story’s observation that the intent of the Founders was to “cut off all chances for ambitious foreigners…” (emphasis added) to insinuate themselves into the office of the presidency simply cannot be squared with the theory that, instead, they intended only to cut off “some” chances or even “half of the chances” of such attempts by adopting an interpretation of the eligibility clause allowing but one or the other – but not both – of the parents of a child claiming “natural born Citizen” status to suffice.

THE FAILURE TO ADDRESS MINOR V. HAPPERSETT

Finally, the CKC’s failure to address or even cite the Supreme Court decision in Minor v. Happersett should cause concern in anyone interested in arriving at a “full picture” of what position the United States Supreme Court has taken on these eligibility clause issues. Even the CRS products composed by Mr. Maskell saw fit to cite and address the decision, albeit in highly dismissive and pejorative fashion.

Rather than unnecessarily extend here these remarks with respect to the Minor decision, interested readers may wish to examine prior posts here at The P&E addressing the case in more detail here and here.

In short, the CKC conclusion that the Founders intended that only one parent needed to be a citizen at the time of birth in order to bestow status as a “natural born citizen” upon that parent’s child cannot be squared with the reasoning of the Supreme Court in Minor. And despite the circumstance that the decision in Minor has been abrogated by the Nineteenth Amendment – not to be confused with an overruling of same, which could only be achieved by the Supreme Court itself –, the fact is that, as stated by the Court in Minor, 88 U.S. at 167-168: there has never been any doubt that a child born here to two citizen parents was a “natural born citizen.”

As to children born to parents, one of whom was a citizen and one who was not, or born to parents without regard to their citizenship, the Court in Minor noted there were “doubts.” Id. However, as to children born to parents who were both citizens at the time of birth, which the Court recognized as being “natural-born citizens,” there had never been any doubts as to their status.

Again, when faced with the choice of erecting a “barrier” which was designed to “cut off” not some, but “all” foreign ambitions to the presidency, would the Founders have chosen or intended a standard that would have allowed a 50% chance that foreign influence could exist, the conclusion seemingly advocated by the CKC? Or would the Founders have chosen or intended the higher 100% bar of requiring both parents to be citizens at the time of birth as a condition of “natural born Citizen” status? The CKC posits the former; this writer posits the latter.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the CKC’s use of the term “refreshingly clear” to describe the Constitution’s meaning on the eligibility issue has the same disturbing ring to it as does “the most transparent administration in the nation’s history” as a descriptor of the opacity of the current executive regime.

The likelihood is that, on the remote chance that prior to the 2016 general election, the Supreme Court will summon the courage to actually address the issue of presidential eligibility under Art. 2, Sec. 1, Cl. 5 of the Constitution and stop “evading” the issue, a not improbable opinion could issue – perhaps even a unanimous one – holding that, as Messrs. Maskell, Clement and Katyal contend, a “native born citizen” is “good enough” to meet the “natural born Citizen” constitutional requirement.

If the decision in the Wong Kim Ark case is correct, then unquestionably, Senator Cruz – as well as Senator Marco Rubio and former Senator Rick Santorum – are, at minimum, “native born citizens” under the Fourteenth Amendment. But whether the Founders would have seen see that as “good enough” to satisfy what they intended when they used the term “natural born Citizen” to bar – not just impede – foreign influence from the office remains to be seen. The answer to the question, respectfully, is anything but “refreshingly clear,” and only a binding decision of the Supreme Court will remove the lingering doubts.

On the other hand, and lamentably, now that the first Democrat usurper-chief executive in the Nation’s history is close to completing his term in office – unless he is drafting an executive order declaring martial law and suspending the Twenty-second Amendment –, with no meaningful potential for impeachment before January 2017, what harm could it do to give a Republican the opportunity to do the same? The Supreme Court could use Mr. Maskell’s CRS documents as a template for an opinion ratifying the current president’s eligibility as well as confirming Senator Cruz’s eligibility…, minus, of course, the grammatical ellipsis editing of its decision in Perkins v. Elg, 307 U.S. 325 (1939) in the CRS documents as more fully addressed here.

On the other hand, and lamentably, now that the first Democrat usurper-chief executive in the Nation’s history is close to completing his term in office – unless he is drafting an executive order declaring martial law and suspending the Twenty-second Amendment –, with no meaningful potential for impeachment before January 2017, what harm could it do to give a Republican the opportunity to do the same? The Supreme Court could use Mr. Maskell’s CRS documents as a template for an opinion ratifying the current president’s eligibility as well as confirming Senator Cruz’s eligibility…, minus, of course, the grammatical ellipsis editing of its decision in Perkins v. Elg, 307 U.S. 325 (1939) in the CRS documents as more fully addressed here.

Besides, to rule that the Founders intended that only a person born here to two citizen parents would be eligible as a “natural born Citizen” would severely undermine the razor-thin cosmetic legitimacy of the current president’s administration and potentially render each and all of his actions – from the signing of laws to vetoes to appointments to executive orders – void ab initio, as if they had never occurred, akin to the annulment of a marriage. Such a result, of course, would be tremendously disruptive to the “order” of things and upsetting of the Constitution’s goal of ensuring “domestic Tranquility” and thus, potentially quite problematic.

Accordingly, do not be surprised if the Court turns to the same principle noted at the beginning of this post and the one to which most politicians always turn: expediency. And if you think that could not happen… ingest some more caffeinated fluids and watch the evening news.

Sad.

If you will please pardon the comparison, I personally think Mr. Putin would also make a great President. He has repeatedly shown patriotism, strength of character, and … stays true to his publicly stated convictions. As a P.S. – according to the Harvard lawyers, “the law doesn’t mean what it says; it means what we say it says”.

Isn’t it ironic that it could be Ted Cruz to be the one to be responsible for killing the Constitution for good, and not Barry Obama.

Fate is indeed fickle.