NONAGENARIAN SHARES MILITARY, LIFE EXPERIENCES, VIEWS ON WHAT AMERICA NEEDS NOW

by Sharon Rondeau

(Dec. 22, 2015) — Several weeks ago, Dr. Tom E. Davis contacted The Post & Email with a number of submissions for our Editorial column, in response to which we sent him our guidelines and requested a brief resume or biography.

Upon reviewing his “short bio,” we noted that Dr. Davis is nearly 91 years old, which makes him a “nonagenarian.” We read with interest that he served in the U.S. Army in the China/Burma/India theater during World War II and were instantly fascinated based on a family connection to that operation.

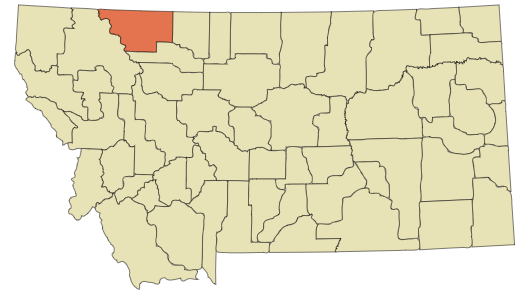

Dr. Davis was born in January 1925 in Kerrville, TX and moved to Cut Bank, MT when he was eight years old. He has published four books: “Federalism vs. Factionalism: How the Democratic Party Raped the Republic;” “America’s First Female President…2016;” “Peregrinations: How the Davises Overran America;” and “My Conservatory,” an anthology of human-interest stories collected over Dr. Davis’s lifetime.

His original goal in writing “Federalism” was to produce a short pamphlet, although the work grew to 111 pages.

We had many questions to ask Dr. Davis, beginning with his military service.

THE POST & EMAIL: You were in the China/Burma/India theater, where my dad was. Would you mind talking about that?

DR. DAVIS: I wouldn’t mind at all, but let’s go back a little bit.

When I got out of high school in Cut Bank, Montana, there were really no good jobs. The war was on, and most of the grown men had gone off to war. So I took a job on the Great Northern Railway on a road gang. I was a gandy dancer, which is an individual who works on the railroad leveling track, installing track or removing track. I weighed 117 pounds, and I was carrying what they called a jack tamper; it had a blade about nine inches wide and vibrated like a jackhammer.

My brother and I were a team; he worked on one end of a given tie on the railroad, and I worked the other. As we were working, men went alongside and shoveled gravel right in front of the blade so we could tamp it. Another guy had wedged it in order to level the track.

Roy Brown was the gang chief; he was a great man. We leveled track all day long, ten hours a day, for $.50/hour. The going pay rate at that time was $.25 an hour, but he was paying $.50 an hour, so it was a better job than watching your brother’s grocery store or something.

As I was doing that, I got to thinking — my dad got a letter from his brother, who said he was going to work for Sims, Drake Puget Sound. It was a construction company that was going to rebuild the naval base at Women’s Bay in Kodiak Island, Alaska. My dad said he was going to see Uncle Coral, and I said, “Can I go with you?” He said, “What do you want to do?” and I said, “I want to see if I can go to Women’s Bay and get a job up there, do something for the war effort.” So he said, “Sure.”

My dad was pretty heavy on the bottle; he liked to do a little drinking. We went out to Seattle and met Uncle Coral, and then my dad said, “Go stay at the hotel; get some sleep,” and they went out and got flaming drunk. The next morning, I saw my dad – he was drunk as hell – and he said, “I’m going back to Cut Bank; what are you going to do?” and I said, “I’m going to stay right here and see if I can get a job with Uncle Coral.”

My dad left, and I cried like a baby.

SR: And you were 18 at the time?

DR. DAVIS: Seventeen. That was the first time I had been deliberately left alone. On the way home, he had a car wreck; he got out OK. I went down to the Puget Sound employment office and they said, “You’re too young, son. You have to be 18 to be on this job.” So I said, “Well, the hell with you.” I went over to the Merchant Marine headquarters and said, “Can I get out on a ship?” and he asked, “How old are you?” I said, “Seventeen,” and he replied, “Yeah, you’re old enough. Do you have identification?” and I had identification. I got my seaman’s papers, which I still have, and I was signed on as a wiper, which is the lowest rank on a ship. It’s an engine room job keeping the decks clean.

All the ships in those days were what they called “three-legged, up-and-down” jobs. So they assigned me to a ship for the day, where I shoveled coal while they were working on their ship. I said, “The hell with this; I don’t really want to shovel coal all day unless it’s going somewhere.” That ship was sunk during the war.

I went back to the Marine headquarters and said, “Can you get me out on a ship?” and they said, “Do you really want to go out?” and I said, “Absolutely.” They said, “You don’t have much experience,” and I said, “I’ll get some experience on the ship.” So they assigned me to the William L. Thompson, which was an old post-World War II ship, a three-legged, up-and-down job that had three steam heads. The smallest one took the first shot of steam, but it was very condensed. Then it went up to three bigger heads. They would drive pistons which would turn the propeller.

So they put me on there as a wiper. I went down and met the guy in charge – I wrote an article about him – he was a bull wiper. He had been sunk three times in the Atlantic run and survived all three of them. He was always well-dressed, in khaki, and he said, “Welcome aboard, son.”

I got on that ship, and that evening, we pulled away from the dock and headed out into the Strait of Juan de Fuca. We started in what they call the “Inside Passage.” We had a Canadian cutter that protected us while we were out in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, just outside. It was rough as hell. That ship was a little tiny boat, and the next morning, it was gone. It left us, and we were inside the passage. We stopped at Ketchikan, Skagway, several different places – beautiful, beautiful scenery, glaciers, a gorgeous area.

Then the captain announced on the loudspeaker, “Gentlemen, we are about to enter Cape Spencer,” the outlet into the North Pacific.

We didn’t realize, though we should have, that the Japanese controlled that water. So we had to be on the lookout. We had a Navy gun crew with three big guns, and we went outside of Cape Spencer and headed for Kodiak Island. We docked in Kodiak, and the chief engineer asked who wanted to take a leave and go ashore. Then he said, “Actually, we’re going to leave one wiper with one engineer,” so it would be just two people. So I said, “I’ll stay on board.” The bull wiper then told me, “Tom, you don’t really want to go aboard; get off the ship; there’s nothing but prostitutes and whiskey. So I said, “OK, fine.”

Out of nowhere I heard a whistle, and somebody said, “Whew!” He said, “Can you start the donkey engine?” and I said, “Sure.” He said, “We’re going to need a little power; we’ve got to make a move.” The telegraph, which is a signaling device from the Bridge to the Engine Room and signals such orders as “Ahead Slow,” “Ahead half,” “Ahead Full,” “Stop,” “Astern slow,” etc. suddenly moved and said, “slowest turn,” and I signaled back, “OK.” I had to run around a partition to get to the donkey engine in order to feed it a little bit of oil, fire it up so we could make a move. I got that going and heard a whistle, and somebody yelled, “What’s happening down there?”

I couldn’t control it as fast as he wanted it controlled by myself. We knocked over a couple of pilings, but no damage was done. And that was my experience in operating a ship.

We made our way back across the North Pacific; the gunners were on the alert, as they said they saw a submarine periscope.

————————

Dr. Davis’s story will be continued in a second installment.