by ProfDave, ©2022

(May 26, 2022) — [Editor’s Note: The following is the 20th in a series of world history lessons, converted to written form, by Prof. David Heughins. For previous articles in this series, please go here.]

Time out! We are a month into our survey of modern World Civilization and we’ve hardly got out of Europe! Three reasons: developments in Europe were pretty fascinating between 1648 and 1900, Europe led the rest of the world during this period, and your professor majored in European history.

East Asia in Early Modern Times: Qing China

European contact with China began with Portugal, under the Ming dynasty, in 1514. Trade patterns were well established by the 17th century, funneled through the port of Macao. Portugal brought gold and silver in exchange for Chinese silk, tea, and china under narrow restrictions. Portuguese Jesuit missionaries sought to adapt Christianity to Confucian forms – with some success, until Spanish Franciscans and Dominicans reported them to the Pope. Other European nations followed, and the Spanish came with bullion direct from Mexico and Peru. But there was a balance of payments problem that only got worse: China was not interested in Western goods [Duiker & Spielvogel 483-85].

As Chinese dynasties eventually do – every 300 years or so – the Ming began to crumble in the late 16th century. Weak rulers confronted a series of crises, natural and self made. The silver trade upon which Chinese currency had come to depended was disrupted by British and Dutch pirates. The early 17th century brought a “little ice age” to the whole northern hemisphere. Crops failed, corruption hampered response, taxes went up while services went down, and northern peoples raided over the wall. Finally, an epidemic sparked a peasant revolt and drove the last Chinese Emperor to suicide in 1644. The peasants tried to put forth a leader but were overwhelmed by a Manchu invasion [Duiker & Spielvogel 485-86].

The foreign invaders from Manchuria set up a new dynasty, the Qing, and enforced submission. A mark of that submission on all males was the famous queue. “Lose your hair or lose your head:” the front of the head was to be shaved and the back tied up in a single braid. And you thought that was a Chinese stereotype. The Manchu constituted a separate elite of perhaps 2% of the population, but soon adopted traditional Confucian forms of government, pairing their own people with Chinese counterparts at the top levels. There followed perhaps the greatest age of Chinese power and prosperity under two particularly able and long reigning Emperors [Duiker & Spielvogel 486-87].

Kangxi (1661-1722) came to the Empire as a child, but became a man of character, particularly diligent and astute. He embodied classical Confucian principles. Qianlong (1736-95) showed equal ability and intelligence. The Empire reached its height of power and glory and the state its greatest prosperity, efficiency, and excellence. But in his later years there were signs of trouble. Military expenses were mounting. A quota system, applied to the traditional Confucian civil service examination system to assure representation of all regions and minorities, opened the door to corruption. Decades of internal peace, stability and agricultural revolution (new and better rice, New World peanuts, corn and yams) had led to a population explosion. China had grown from 200 to 300 million while Europe had grown from 120 to 200 million. There had been commercial growth, but it was discouraged by the cultural preference for antiquity, leading to a technological gap with the West (China had been far ahead in the Middle Ages). Then there was the European problem. China was not willing to deal with western nations as equals. Western manufacturers needed markets to sustain industrial growth (factories closed, causing social problems, if the goods were not sold) and chafed at Chinese restrictions on trade. China wanted silver – cash – not western goods. Confucian thought resisted change and “progress” [Duiker & Spielvogel 487 ff, 643-44].

Tokugawa Japan was finally unified in 1603 after a century of feudal anarchy and disunity. Portuguese contact had already been established, facilitated by Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier who arrived in 1549 and was virtually given the port of Nagasaki. Unlike the Chinese, the Japanese were eager for European technology and particularly weapons from the first. Christianity also met with success until Spanish Franciscans led to conflict and mass crucifixions mid 17th century, followed by drastic limitations on trade and foreign travel. Even more than China, Japan became a closed society. The Tokugawa Shoguns were great lords who ruled in the name of the emperor. They were assisted by a council of Daimyo (provincial lords), who were nominally independent and lived on the taxes of their provinces. These were supported by a warrior elite of Samurai. A century of peace led to great growth of industry and commerce, and the beginnings of banking and capitalism. Power was increasingly centralized and the Samurai were economically squeezed by their traditions, but remained politically and socially important [Duiker & Spielvogel 497ff].

In Southeast Asia, the Dai Viet Empire expanded by conquering Champa and the remnants of the Angkor civilization, reaching the Gulf of Siam. But in the 17th century it suffered civil war and was only united with French assistance under the Nguyen dynasty, from the South. The capital was moved to Hue, as a bridge between the two rivers (the Red and the Mekong). Efforts to maintain Confucianism against French Catholicism were to become an issue of contention for the future [Duiker & Spielvogel 508].

Nineteenth Century Asia: the Indian Raj

The Mughal Empire was but a shadow by 1800. India was ruled by the British government or client states. They provided the subcontinent with peace, education, railroads, postal service, and an end to thugee (systemic banditry). But the native textile industry had been destroyed by the factories of England (like every other nation’s less developed textile industry). Industrialization was slow, land policy wrong-headed, and little progress was being made towards democratic institutions during this century [Duiker & Spielvogel 618-20].

Southeast Asia in 1800, began with the Dutch East Indies and the Spanish Philippines already established. The British founded the city of Singapore in 1819 and extended their influence over Malaysia then Burma in 1826. France followed its missionaries into Vietnam in 1839 and came to dominate Cambodia and Laos by the end of the century. Thailand skillfully avoided Western control by playing the British off against the French. The Dutch worked amicably with the local aristocracy, as did the British in Malaysia. Singapore itself, however, was a British city, and Burmese royal resistance led to direct British rule from India. The French ruled southern Vietnam directly but worked through the emperors and local authorities elsewhere. Attempts at broad western education were short lived. There were few positions open to an educated Vietnamese: “one less coolie, one more rebel.” Better child health led to a population explosion in the region, but economic development lagged. Industry grew up in Rangoon, Batavia, and Saigon but most of the businesses were in foreign hands – Chinese or Indian, if not European – and reinvestment tended to go the home country of the investors. Plantation agriculture produced rubber for export. On the whole, conditions were better in 1900 than in 1800, but the region did not achieve the full benefit of modernization [Duiker & Spielvogel 621-26].

The Decline and Fall of Manchu China was accelerated but not caused by Western imperialism. After a century of powerful rulers, the familiar pattern of incompetence and corruption set in. The population had doubled and was still growing, but the Confucian elite still looked to the ancients and not to modern solutions as the technological gap widened. Meanwhile foreign troubles became critical. British merchants, chafing under arbitrary restrictions and an impossible balance of payments hit upon opium, grown in northwest India for medicinal purposes, as a solution. When this became an alarming drug problem in China, the court launched what was perhaps the first war on drugs in 1839. A confrontation occurred over the searching of British warehouses and destruction of stocks, leading to a naval expedition and the so-called Opium War (1839-43). China was completely humiliated, forced to open new trade concessions and cede Hong Kong to the British. Western influence was only indirectly involved in the Taiping Rebellion (1853-64) – really caused by hunger and taxes. But conflict erupted periodically from 1856-60 with Britain and France, leading to more humiliating concessions [Duiker & Spielvogel 644-47].

Finally, the Manchus responded with “Self-strengthening Reforms,” a program of reemphasizing traditional values, but accepting modern western technology. Perhaps it was too late. China was humiliated again in a war with Japan over Korea in 1894 and a confrontation with Germany in 1897. Europe rushed to exact new concessions, each compensating for concessions to the other.

The emperor turned to liberal Kang Youwei to enact sweeping changes, but the emperor’s aunt, a powerful figure behind the throne, imprisoned the emperor and Kang Youwei fled for his life. The Empress Dowager Cixi, despite her conservative views, was forced to accept reforms. At this point, US Secretary of State John Hay intervened. American merchants were as anxious as anyone else for commercial opportunities in China, but not for Chinese collapse and partition. Hay was able to negotiate a truce among imperialists, called the Open Door Policy, to guarantee the independence and integrity of the Chinese state. So the Manchu Empire struggled on until 1911 [Duiker & Spielvogel 647-52].

Sun Yat-sen (1866-1925) was an American-educated Chinese doctor and founder of the reformist Revive China Society among urban intellectuals. It was later expanded into the Revolutionary Alliance, based on “three peoples’ principles:” nationalism (against the Manchu as a foreign regime), democracy, and livelihood (economic reform). The plan was for a military takeover, leading by stages to democracy. The revolution occurred in some provinces in 1911, unfortunately while Sun was out of the country. In his absence, the rebels chose a dissident, but conservative, General Yuan Shikai. He had been sent by the Manchu to suppress the revolt, but during negotiations agreed to lead them instead. Though the Alliance had limited popular support, they were able to drive out the Manchu and establish a republic [Duiker & Spielvogel 652ff].

The Meiji Restoration of Japan was not much of a restoration. The Meiji had been emperors for centuries and they still were. The Tokugawa Shoguns had for two centuries ruled Japan in their name but were becoming rigid and corrupt. For two hundred years Japan had been even more isolated than the Chinese, dealing only with Korea. Then the black ships came in 1853, under Commodore Perry, politely but firmly demanding trade relations. Unlike their Chinese neighbors, the Japanese court recognized the military and technological superiority of the visitors immediately. The Shogun made the decision to open Japan to western trade, but it was intensely unpopular in the provinces. The Daimyo of Satsuma and Choshu rose in rebellion, 1863-68, and toppled the regime [Duiker & Spielvogel 657-59].

Although the “Sat-Cho” Daimyos were really in charge, they professed to restore absolute power to the Meiji Emperor and everything was done in his name. Once in power, however, they quickly recognized the realities of Western superiority and launched upon a career of comprehensive change – or was it? In forty years Japan was transformed from a traditional to an industrial society. For cash compensation, the feudal Daimyos lost their hereditary privileges and became appointed provincial governors. For cash compensation the feudal samurai were abolished (?) and forbidden to wear their swords. The emperor and court officials swore the Charter Oath promising parliamentary monarchy and civil equality. It took two decades, however, to produce a constitution, and – after a great deal of debate – it was patterned after Bismarck’s Germany, rather than the United States: democratic in form, but despotic in practice [Duiker & Spielvogel 659-60].

When the dust settled, the same people dominated different institutions, but the values and the theory had changed. The elite changed uniforms but kept power on a new and modernized basis. Land reform produced new taxes used to sponsor industrial development, a new army was raised on universal conscription, education was modeled on the United States (and included women for the first time). But the foundation was still in Confucian values. Individual rights were not guaranteed in the Civil Code of 1898. Meanwhile, Japan pursued an aggressive imperialist foreign policy, intervening in Korea and Taiwan in 1895 (eventually acquiring both), and launched a surprise attack on the Russians at Port Arthur, Manchuria, in 1904. Japanese victory over Russia in that war that was a warning to European confidence – and a step in the collapse of the Tsarist regime. What happened in Japan, initiated as response to Western pressure, was a revolution from above, without violence or class destruction. Urbanization and industrialization were already under way. Japan was soon the major textile producer of Asia – with women making up 60% of the workforce. The pragmatic marriage of feudal loyalty with industrial capitalism was symptomatic of a state dedicated to material wealth and national power [Duiker & Spielvogel 660ff]. Was this Asian Fascism?

The New World before 1914

The first settlers in Mexico called their colony “New Spain” and the first settlers of the north called theirs “New England.” A really really short comparative history of the western hemisphere is encapsulated in those names. Spain was a nation of feudal grandees, huge estates, and servile peons. Its wealth was consumed, rather than reinvested, and work and trade were beneath the dignity of the elites. England was a nation of shopkeepers and small holders, with far less land and far more business. Lords invested the proceeds of their estates shamelessly in trade and industry. The church was monolithic and ubiquitous in Spain, but conservative and subservient to the monarchy. The church in England was factious and fervent, lurching from catholic to reformed to papist to Anglican, spinning off revolutions and dissenters – many of whom emigrated to the “New England.” Christianity in Britain was never quite under control, as both conservative and radical called upon religious passions. And as the home countries, so the colonies. Spanish and Portuguese colonies were characterized by grandees and peons and huge extractive estates while English colonies featured bustling industry and relatively small farms (though large by English standards) [Stark 195 ff].

Latin America in the early modern period, consisted of Portuguese Brazil, assorted British, French, Spanish and Dutch islands in the Caribbean, and four Spanish Viceroyalties: New Spain (Mexico) 1535, Peru 1543, New Granada (Ecuador to Venezuela), and La Plata (Argentina & Chile). Its population was primarily indigenous. Spain had limited immigration to perhaps 300,000, mostly men – and no single women – by 1700. Most of them expected to return to Spain when their fortunes had been made [Stark 213]. The natural result was a considerably larger number of Mestizos (European-American mix-bloods). About eight million African slaves had been imported, mostly to Brazil and the Islands (how many survived?), producing a significant population of Mulattoes (European-African mix) and Maroons (African-American mix). The most important social division however, might have been between the Peninsulars (born and expecting to retire in Spain or Portugal) and the Creoles (born in the New World). The economy rested upon mining and export agriculture, extracted by conscripted labor. Gold was found in the Caribbean and New Granada, Silver in Mexico and Peru. Whole villages were rounded up and compelled to work without pay or even provisions for months at a time. As time went on huge semi-feudal estates, with their thousands of dependent peons or slaves, became even more important, producing sugar, tobacco, hides, and tropical products for export in exchange for supplies and manufactured goods – not from Spain and Portugal, but indirectly from Britain and northern Europe. Spain (and Portugal) attempted to keep the profits and the carrying trade in their own vessels but did not have the naval power to patrol so vast a frontier. This led to a lawless world of interlopers, smugglers, and pirates, condoned and abetted by other powers.

The administration of the Spanish and Portuguese colonies came directly from the mother country. Viceroys, provincial governors, and their officers were appointed by the Crown, came from Iberia, and expected to return when their term of service was ended. So were the Bishops. There were no colonial legislatures. Only local city officials were native-born. Foreign born missionaries attempted to organize Indians into villages to be converted, educated, and taught to grow crops. The church was responsible for hospitals, orphanages, and schools [Duiker & Spielvogel 526]. But the church was a mile wide and an inch deep, served by a small number of mostly foreign clergy to this day. When Pope Paul III excommunicated all slave traders and slave holders in 1537, his bull, by Royal order, was not published in the New World. When the Jesuits published it in 1767, they were quickly expelled from Latin America [Stark 201-202]!

British North America, in 1700, was mostly along the Atlantic coast, including Hudson’s Bay. New France stretched from the mouth of the St. Lawrence to the mouth of the Mississippi, but was very sparsely settled. England was very much under the domination of the rising middle class (some say that it is a law of history that the middle class is always rising, but that is because we only notice them then) by mid-century, and then the industrial revolution began. “New” England was much less class conscious. The addition of Canada and the Mississippi to the British Empire, removing the threat of French invasion, was a major catalyst towards colonial independence. On the other hand, sectional differences remained significant.

Unlike the Spanish colonies, the British and French) colonies attracted a lot more families who intended to stay and make a self-sufficient life and society on this side of the water, relatively like what they had known in Europe, but much better. There was no Creole-Peninsular split and little intermarriage with indigenous people (except perhaps in the Canadian west). Unlike Latin America, northern settlers immediately set up representative institutions, relatively unchecked by traditional elites and often in defiance of instructions from London. Economically, small holder entrepreneurs predominated in the north and a slave holding, plantation, export economy in the south. But the “southern gentlemen” of British North America derived their values from the landed gentry of England – represented in the House of Commons – not from the House of Lords, very different from the Spanish Grandees [Duiker & Spielvogel 526-27].

Latin American Independence movements began as Creole elites were touched by Enlightenment ideas and news of the revolutions in North America and in Europe, particularly the conquest of Spain and Portugal by Napoleon. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in France triggered a revolution in Haiti in 1804 by Toussaint L’Ouverture, complicated by a three-way civil war with Mulattoes, free blacks, slaves and Creoles. Although the economy was ruined, the world’s first black republic was established [Duiker & Spielvogel 536-37, 581-82]. The Mexican priest, Miguel Hidalgo led Indians and Mestizos in an unsuccessful uprising in 1810. Augustin de Iturbide, with Creole support, made himself Emperor of Mexico in 1812. This was not a real regime change. The Enlightenment and Napoleon also inspired Simon Bolivar (1783-1830), a wealthy Venezuelan. He expelled Spanish control 1813-21 from Columbia, Ecuador, and Peru. He became President of Venezuela but failed in his dream to unite all Spanish South America. Argentine Jose de San Martin (1778-1850) was serving in the Spanish army when his country was liberated 1812, but is credited with leading an army over the Andes to liberate Chile. Brazil achieved independence in 1822 and the rest of Central America 1838-39.

After Waterloo, the old order was restored in Europe and there was consideration given by the Concert of Europe to restore Latin America to Spain and Portugal. Russia and Austria advocated such a course, but nothing could be done without the British navy. Britain, long time scofflaw of the Spanish Main with lively interests in Latin American trade, was reluctant. At that point, 1823, American Secretary of State, James Monroe (later President), seized the initiative and guaranteed Latin American independence against European intervention. This is called “the Monroe doctrine” – but in fact depended on the Royal Navy for enforcement [Duiker & Spielvogel 582ff, Craig 23-24].

Most of the work of liberation had been done by and for Creole elites, American born descendents of Europeans who had not returned home with their parents. The wars of independence were expensive, destructive, and left many boundaries in dispute. They were widely scattered across the continent, with primitive transportation and communications infrastructure. Most Latin states started out as republics, on European models, but they had no experience with colonial self-government and slid into Napoleonic autocracy. Conservative caudillos (strong men), representing the Creole elites, centralized government and revenue in their own hands, modernized to some extent, and depended on the church, the rural aristocracy, and the army for support. They alternated with radical caudillos, supported by the masses, who attempted to redistribute the land, break up large estates, and put the church in its place [Duiker & Spielvogel 586-87].

Latin American economy continued in the old patterns, substituting Britain and the U.S. for Spain and Portugal in the exchange of raw materials and food for manufactured goods and textiles. The economies remained largely extractive, dominated by large agricultural estates, and manufacturing was stifled. After 1870 there was rapid economic growth, but still based on a few basic products. There was a boom in foreign investment and railways were built with British funds. Industrialization did not take hold until 1900, but a small urban, educated, “middle sector” was growing, partly due to European immigration. Political change also accelerated after 1870 as Argentina and Chile received new constitutions (albeit with narrow electorates). In Mexico, conservative dictator Porfirio Diaz held power from 1876-1910, but the Revolution of 1910 brought the liberal Francisco Madero to the presidency and the colorful Emiliano Zapata took matters into his own hands, seizing haciendas. With the 20th century, the influence and intervention of the United States became a major factor in Latin affairs as the US “liberated” the last two major Spanish possessions, Cuba and Puerto Rico, in the Spanish American War and intervened repeatedly in the Caribbean region [Duiker & Spielvogel 587-89].

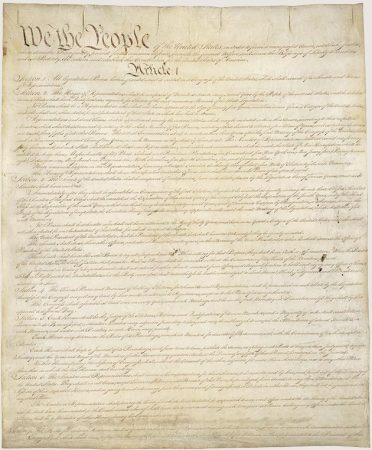

The Rise of the United States is a course in itself. Initially united by opposition to British Mercantilism (taxation, regulation of trade, and restriction of frontier expansion), unity was a major issue for much of the first century. Republicans feared the power of a centralized government while Federalists feared anarchy and mob rule. States differed on financial and foreign policy issues. The Articles of Confederation did not work: there were no common funds for national obligations and no respect abroad. This led to the Constitution of 1789, a careful compromise between a centralized government that could get things done and a federation of independent states that could go their own way. Its balanced powers recognized human depravity – the tendency of power to corrupt – and attempted to prevent both the despotism of the autocrat and the despotism of the popular whim of the masses [see Duiker & Spielvogel 589]

There was something of a split over Napoleon, the Republicans pro and the Federalists anti in the lead-up to the War of 1812. The USA did not fare well, as side-show allies of the French. They failed to conquer Canada (the Canadians were not interested in being conquered, apparently), the British burned Washington DC, and the only American victory, at New Orleans, came after the war was over! That was the end of the Federalists. Andrew Jackson’s democratic “revolution” of 1828 brought a swing in the direction of mass democracy and the dominance of liberalism. But the major divisive issue of the next three decades was slavery [Duiker & Spielvogel 590].

The economy of the Deep South was heavily dependent on cotton exports, grown by some four million slaves by 1860. Earlier generations had been ambivalent about this “peculiar institution.” On the one hand it was widely acknowledged as dissonant with American ideals of liberty and equality. English Methodist founder, John Wesley, was quick to point out the inconsistency of Americans protesting “slavery” to George III while themselves holding black slaves under the lash. On the other, southern patriots did not quite see how they could operate their plantations without this labor force. The religious (second) “awakening” of the early nineteenth century led, especially in the north, to broad spectrum – “every good cause” – effort to apply the Kingdom of God to earthly conditions. The example of the British, French, and Dutch abolition of the Atlantic slave trade and of slavery was taken up by Abolitionists in America. Slavery was abolished in all the north eastern states. A defensive reaction was provoked in the south, exacerbated by fear of slave revolt, and seeking religious and scientific justification.

At the same time, the nation was expanding rapidly to the west. Would the new states there be slave or free – and would their congressional delegations vote to curtail slavery nation-wide? Would the states’ rights to make their own laws and protect their own institutions be respected? What about slaves who ran away to the north? Both sides resorted to terrorism in Missouri and Kansas. The issue destroyed one major party (Whigs) and split the other (Democrats). A third, mostly northern party (Republican – not to be confused with the original earlier one) emerged, and in 1860 elected Abraham Lincoln on a platform of centralism and limitation of slavery. The South seceded and attempted to form a new nation, but Lincoln refused to let them go. The Civil War (1861-65) began as a war of states’ rights and national unity but became in the end a crusade against slavery. The old south was destroyed and an industrial America launched, but Republican reconstruction failed to produce a new south of industry, small farmers, equality and racial harmony – issues that remained unresolved for a century (or more?) [Duiker & Spielvogel 590-92].

The Industrial Revolution took place in the United States between 1860 and 1914. It began in railroads spanning the continent, financed in part by British capital. By 1900 industrial production had outstripped Britain, urbanization had reached 40%, and immigration exceeded 14 million. The USA had become the world’s richest nation, but there was a great gap between rich and poor, urban and industrial conditions were disgraceful (though better than early industrial Europe), immigrant masses threatened Anglo-Saxon homogeneity and Puritan consensus, African-Americans remained an unassimilated underclass, corruption was rife in politics and business and there were many other social problems. Some of these issues were addressed with vigor in the Progressive era following the Spanish American War (1898), but not all [See Duiker & Spielvogel 592-93].

The Establishment of Canada dates back to the fall of New France in 1763. By 1800 it comprised Upper Canada (English Ontario), Lower Canada (French Quebec), New Brunswick and Nova Scotia (with significant French and American loyalist populations). Throughout the nineteenth century Canada was to receive large numbers of British immigrants. Abortive efforts by the United States to include or conquer Canada in the Revolutionary War and in the War of 1812 only served to cement a sense of national distinction, even though unity of Francophone and English – and later Western provinces – remained issues. Rebellions in 1837 were suppressed, but Britain took warning, moving the provinces towards union and self-government. In 1867, prompted by the US Civil War, the British Parliament established the Dominion of Canada with internal self-government under its own parliamentary system. The western provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan were added and in 1885 a transcontinental railroad became an important link tying this vast land mass together [Duiker & Spielvogel 593-94].

Sources

The bulk of these notes refer to Duiker and Spielvogel, others to my current reading, but I confess that some of the ideas have been roaming around in my head for forty years and I am unable to identify their precise origins.

Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism, Cleveland: Meridian Books, 1958.

Unable to identify exact references of Dr. Kieft’s synopsis, see below.

Craig, Gordon A. Europe since 1815. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1961.

Duiker, William L. and Spielvogel, Jackson J. World History, 6th edn., Boston:

Wadsworth, 2010

Gilbert, Martin. Recent History Atlas 1860 to 1960. London, WI: Weidenfeld &

Nicolson, 1970.

Heughins, David W. “The Expansion of Europe,” Post University, (HIS 101 PowerPoint

Lecture, Unit 7) 2011.

Kieft, David. Lectures on Diplomatic History, University of Minnesota, 1971.

Stark, Rodney. The Victory of Reason. New York: Random House, 2005.

David W. Heughins (“ProfDave”) is Adjunct Professor of History at Nazarene Bible College. He holds a BA from Eastern Nazarene College and a PhD in history from the University of Minnesota. He is the author of Holiness in 12 Steps (2020). He is a Vietnam veteran and is retired, living with his daughter and three grandchildren in Connecticut.