AN HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF THE STATES AS INDEPENDENT REPUBLICS

by John Sutherland, ©2010

(Aug. 9, 2010) — America started out as thirteen unfunded yet chartered British colonies, went along for many years in a relatively benign condition of neglect by Britain, developed their own methods of survival, and managed to thrive and prosper in the New World quite well – all without British assistance. As the American colonies thrived, however, Britain started to look at them differently, and sought increasing control over them. The maturing colonies, however, consistently rejected what they perceived as unrepresented interference and taxation by Britain, and through their Declaration of Independence and open military conflict with Britain, sought for themselves to become free and independent of Britain. The colonists were working toward the freedom and independence of statehood. Early definitions defined the statehood clearly – A State was a sovereign political entity, not simply a territory of a government.

The open military hostilities that occurred between British soldiers and the American Colonists on Lexington Green and at Concord Bridge on April 19, 1775, started the American Revolution, sometimes referred to as the War for Independence. Legal separation between the British American colonies and King George III and Britain was formalized with the colonist’s Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, which declared the former British colonies as new sovereign states in America.

“We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.” [Emphasis added]

Two years later, on July 9, 1778, the Second Continental Congress approved and adopted the Articles of Confederation, thus creating the formal and legal government of these United States of America. The Articles included one up-front section regarding state sovereignty:

Article II. Each State retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this confederation, expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled. [Emphasis added]

Notice that every single former colony is now referred to as a sovereign state, with all rights and powers of an independent country. The confederation of states was identified as the united States of America – not as a united single state of America – but as a confederated republic of many sovereign states.

The war between these new united States of America and Great Britain was fought from 1775 until 1783, when final terms of peace between the two countries was declared in Paris. The ‘Paris Treaty’ was signed on September 3, 1783, and was ratified by Congress on January 14, 1784, formally ending the American Revolutionary War between the Kingdom of Great Britain and the United States of America.

Article 1 of the Paris Treaty individually lists all of the former colonies as ‘free sovereign and independent states.’ The sovereignty of the individual states was thus clearly understood and proclaimed by both parties signing the treaty:

“His Brittanic Majesty acknowledges the said United States, viz., New Hampshire, Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia, to be free sovereign and independent states, that he treats with them as such, and for himself, his heirs, and successors, relinquishes all claims to the government, propriety, and territorial rights of the same and every part thereof.”[Emphasis added]

Although France, Holland, and Morocco were among the first nations to recognize the fledgling republic, this may have been the first official recognition of the United States of America by Britain.

Remembering that the new ‘country’ was a confederation of sovereign states, the controlling document ‘Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union’ (in force from March 1, 1781, until the present Constitution) had set up a very weak central government, and the new central government’s failings were sometimes overwhelming in frustration for the states.

The ‘Articles’ primarily had problems with currency (money), interstate commerce, foreign trade, and foreign affairs. Many states printed their own money, and the national currency became almost worthless. Some states placed tariffs on each other’s goods, which, when combined with currency problems, led to a decline of interstate commerce. Foreign nations placed tariffs and trade restrictions on American goods, and the country was simply not able to respond. America had no navy, and this left merchant ships vulnerable to pirates. The Treaty of Paris, which had ended the Revolutionary War, was not enforced by the United States, and as a result, the British continued to occupy forts in the Northwest Territory – a part of the US. The government was a unicameral legislature only – there was no executive branch or court system. Each state only had one vote in the legislature, no matter how big the state was. The government required a 2/3 majority to pass legislation, and amending the articles required a unanimous vote. Etc., etc.

While operating under the Articles of Confederation, the states had developed a sense of impending disaster, and the need for drastic changes in the new government pervaded the Constitutional Convention that began its deliberations in Philadelphia on May 25, 1787. James Madison and Alexander Hamilton were convinced that a more powerful and effective constitution with a wide range of enforceable powers must replace the impotent and failing Articles of Confederation originally set up by the Congress of the Confederation.

After months of work, the new ‘Constitution for the United States’ was completed and signed by the delegates on September 17, 1787. It was then sent to the states for ratification. Article VII of the new constitution stipulated that nine of the thirteen states had to ratify the constitution before the new government would go into effect for the participating states. By June 21, 1788, and after much debate, nine states had ratified the new constitution, leaving only Virginia, New York, North Carolina, and Rhode Island waiting to ratify.

During this process, John Adams noted that, “I expressly say that Congress is not a representative body but a diplomatic body, a collection of ambassadors from thirteen sovereign States….”

On the same day the Constitution was published, and immediately beside it in the New York newspapers, there appeared the first attack against the new Constitution signed by CATO, secretly known as Governor Clinton. From that point onward, many of New York’s powerful political figures came forward to anonymously attack the new Constitution, all writing under pen names of renowned Romans. Thus began the great public debate, with Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay defending and promoting the new Constitution by way of their own writings and arguments in The Federalist Papers.

The Federalist Papers

Starting in October, 1787, there were a total of 85 Federalist Papers (over 193,400 words) penned and signed ‘Publius’ (after Publius Valerius Publicola, a great defender of the ancient Roman Republic). Hamilton ghost authored 51 of the papers, Madison wrote 26, Jay wrote 5, and three papers were written jointly by Hamilton and Madison. These authors of The Federalist had varying, and sometimes clashing, ideas about the new government, but they all agreed strongly on certain fundamental ideas: republicanism, federalism, separation of powers, and free government.

James Madison, in Federalist Papers 40-44, introduced the concept of dual sovereignty, and in this concept, the new federal government, defined under the new constitution, would be sovereign within its designated powers, and the states would retain all other powers not expressly denied by the Constitution.

Regarding state sovereignty, let’s look at several representative essays in the Federalist papers that include discussions and arguments in support of state sovereignty and supremacy.

The Federalist No. 9 [Alexander Hamilton] – The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection

“Should a popular insurrection happen in one of the confederate states the others are able to quell it. Should abuses creep into one part, they are reformed by those that remain sound. The state may be destroyed on one side, and not on the other; the confederacy may be dissolved, and the confederates preserve their sovereignty.”

And:

“The definition of a confederate republic seems simply to be “an assemblage of societies,” or an association of two or more states into one state. The extent, modifications, and objects of the federal authority are mere matters of discretion. So long as the separate organization of the members be not abolished; so long as it exists, by a constitutional necessity, for local purposes; though it should be in perfect subordination to the general authority of the union, it would still be, in fact and in theory, an association of states, or a confederacy. The proposed Constitution, so far from implying an abolition of the State governments, makes them constituent parts of the national sovereignty, by allowing them a direct representation in the Senate, and leaves in their possession certain exclusive and very important portions of sovereign power. This fully corresponds, in every rational import of the terms, with the idea of a federal government.”

The Federalist No. 31 [Alexander Hamilton] – Concerning the General Power of Taxation (continued)

“The State governments, by their original constitutions, are invested with complete sovereignty.”

The Federalist No. 32 [Alexander Hamilton] – Concerning the General Power of Taxation (continued)

“An entire consolidation of the States into one complete national sovereignty would imply an entire subordination of the parts; and whatever powers might remain in them, would be altogether dependent on the general will. But as the plan of the convention aims only at a partial union or consolidation, the State governments would clearly retain all the rights of sovereignty which they before had, and which were not, by that act, exclusively delegated to the United States. This exclusive delegation, or rather this alienation, of State sovereignty, would only exist in three cases: where the Constitution in express terms granted an exclusive authority to the Union; where it granted in one instance an authority to the Union, and in another prohibited the States from exercising the like authority; and where it granted an authority to the Union, to which a similar authority in the States would be absolutely and totally contradictory and repugnant.”

And:

“The particular policy of the national and of the State systems of finance might now and then not exactly coincide, and might require reciprocal forbearances. It is not, however a mere possibility of inconvenience in the exercise of powers, but an immediate constitutional repugnancy that can by implication alienate and extinguish a pre-existing right of sovereignty.”

The Federalist No. 39 [James Madison] – Conformity of the Plan to Republican Principles

“But if the government be national with regard to the operation of its powers, it changes its aspect again when we contemplate it in relation to the extent of its powers. The idea of a national government involves in it, not only an authority over the individual citizens, but an indefinite supremacy over all persons and things, so far as they are objects of lawful government. Among a people consolidated into one nation, this supremacy is completely vested in the national legislature. Among communities united for particular purposes, it is vested partly in the general and partly in the municipal legislatures. In the former case, all local authorities are subordinate to the supreme; and may be controlled, directed, or abolished by it at pleasure. In the latter, the local or municipal authorities form distinct and independent portions of the supremacy, no more subject, within their respective spheres, to the general authority, than the general authority is subject to them, within its own sphere. In this relation, then, the proposed government cannot be deemed a national one; since its jurisdiction extends to certain enumerated objects only, and leaves to the several States a residuary and inviolable sovereignty over all other objects.”

And:

“In requiring more than a majority, and particularly in computing the proportion by States, not by citizens, it departs from the national and advances towards the federal character; in rendering the concurrence of less than the whole number of States sufficient, it loses again the federal and partakes of the national character.”

The Federalist No. 40 [James Madison] – On the Powers of the Convention to Form a Mixed Government Examined and Sustained

“Do these principles, in fine, require that the powers of the general government should be limited, and that, beyond this limit, the States should be left in possession of their sovereignty and independence? We have seen that in the new government, as in the old, the general powers are limited; and that the States, in all unenumerated cases, are left in the enjoyment of their sovereign and independent jurisdiction.”

The Federalist No. 41 [James Madison] – General View of the Powers Conferred by The Constitution

“That we may form a correct judgment on this subject, it will be proper to review the several powers conferred on the government of the Union; and that this may be the more conveniently done they may be reduced into different classes as they relate to the following different objects: 1. Security against foreign danger; 2. Regulation of the intercourse with foreign nations; 3. Maintenance of harmony and proper intercourse among the States; 4. Certain miscellaneous objects of general utility; 5. Restraint of the States from certain injurious acts; 6. Provisions for giving due efficacy to all these powers.”

Judicial Supremacy

There is one more important area of sovereignty that needs addressing, namely that of resolving legal disputes between the states and the federal government, and this topic directs our focus to the final justification for considering the states as sovereign entities.

Under the Constitution itself at Article III, Section 2, we have the following statement:

“In all cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, and those in which a state shall be party, the Supreme Court shall have original jurisdiction. In all the other cases before mentioned, the Supreme Court shall have appellate jurisdiction, both as to law and fact, with such exceptions, and under such regulations as the Congress shall make.” (U.S. Constitution, Article III, Section 2)

This treatment of the states by the Constitution as being of similar legal status of [foreign] ambassadors and public ministers, confirms Samuel Adams’ position that Congress is a body composed of ambassadors from the states of the Union. Retired attorney Publius Huldah notes that Hamilton, a dedicated Federalist, acknowledges this in Federalist Paper number 81 where he discusses the sovereign representatives:

The Federalist No. 81 [Alexander Hamilton] – The Judiciary Continued, and the Distribution of the Judicial Authority

“…Let us now examine in what manner the judicial authority is to be distributed between the supreme and the inferior courts of the Union.

The Supreme Court is to be invested with original jurisdiction, only “in cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers, and consuls, and those in which A STATE shall be a party.” Public ministers of every class are the immediate representatives of their sovereigns. All questions in which they are concerned are so directly connected with the public peace, that, as well for the preservation of this, as out of respect to the sovereignties they represent, it is both expedient and proper that such questions should be submitted in the first instance to the highest judicatory of the nation. Though consuls have not in strictness a diplomatic character, yet as they are the public agents of the nations to which they belong, the same observation is in a great measure applicable to them. In cases in which a State might happen to be a party, it would ill suit its dignity to be turned over to an inferior tribunal…” [Emphasis Added]

Former ambassador and presidential candidate Alan Keyes agrees, and makes the following additional points:

“Why must sovereign entities [states] be dealt with only at the highest level of government? When dealing with foreign entities, such careful courtesy is intended to guard against misunderstandings or insults that, however slight in themselves, can be magnified by passion or calculation into costly confrontations, international incidents or war. Though the relatively permanent civil peace of the United States tempts us to forget it, the same threat lurks beneath the formal arrangements of civil government. In addition to respecting true principles of justice, the whole purpose of the statesmanship involved in the Constitution of the United States is to extenuate this threat by providing a framework for government that anticipates its usual causes and deals with them by peaceful means.”

Such misunderstandings and insults were a precursor of our War of Independence and our War Between The States. Given this, and understanding that the federal government knows very clearly the Constitution and its controls about the ‘court of proper jurisdiction’ when dealing with the States, why has the federal government chosen to sue Arizona in a federal district court, rather than in SCOTUS, in its current dispute regarding protecting our country’s borders? Is this an attempt by the federal government to marginalize the power and sovereignty of the State of Arizona? Similarly, the question of why did the State of Virginia file its lawsuit against unconstitutional and forced federal medical insurance in the federal district court instead of filing it in SCOTUS – does Virginia not recognize its own supremacy?

The Sovereign States vs The Federal Government

This whole subject of sovereignty begs the question of what happens when the federal government acts outside its limited powers, or what happens when the federal government improperly executes its limited functions in such a way that one or more of the sovereign states, and/or the state’s citizens, suffer harm as a result.

The Tenth Amendment to the Constitution was the state’s original attempt (one might argue a futile attempt) to provide pre-emptive protection for the people from an onerous and tyrannical federal government:

“The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.”

I’m certain that many of us have observed that there is little motivation for the federal government to monitor and control or limit its own actions (because there are no penalties imposed on individuals for violating their oaths of office, or on groups for acting in an unconstitutional manner), and as long as this condition is true, the federal government will continue to grow and become more powerful at the expense of the states and of the people. The states are the proper and necessary force required to control, contain, and limit the federal government which they themselves created in 1787.

As an example of state opposition to errant federal activity, in 1798 the Federalist Party controlled Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts which provided individual criminal penalties for any type of speech that brought the president [John Adams] or the [Federalist] congress into disrepute. Aimed primarily at the press, several members of the press were ultimately prosecuted under the law. Aside from the Acts being unconstitutional and in clear violation of the First Amendment, they were politically motivated and wrong headed as hell. This angered Madison and Jefferson enough so that they each authored the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions. In Jefferson’s view, no part of the federal government mattered when compared to the people or to the states. As Jefferson noted:

“whensoever the general government assumes undelegated powers, its acts are unauthoritative, void, and of no force…”

Interestingly enough, public debate created by Jefferson and Madison was a natural first step in confronting the miscreant Adams federal government, and their actions were successful in controlling that particular incident. But what happens if public debate doesn’t solve the problem?

[JS side note: Remembering the 2009 Tea Party protest of one million or more American citizens in Washington DC protesting federal actions, and the complete shunning and the total disregard of the citizen protestors and their message by the Washington elite, what would have happened if the marchers had instead gone en masse to their own state capitals? Would there have been a more significant response? The people’s answers will come from the states – not from the federal government.]

Continuing on, the next stage in resistance to federal tyranny or outlaw activity would likely be the pursuit of legal action in the Supreme Court (as noted earlier, SCOTUS is the court of proper jurisdiction for conflicts involving the states), and if unsuccessful, followed by the states nullifying the federal acts or actions in either a subtle manner (i.e. simply ignoring the federal act) or in a more confrontational manner by convening a statewide nullification convention and declaring publicly the federal act nullified as was done by South Carolina in 1832.

As a final response to federal government unlawful behavior, and when the public debate, the judicial actions, and state nullification are not applicable or simply don’t work, there remains the ultimate option of secession by the states. In other words, if a federal action is deemed by the state to be unconstitutional, the state has the power, and the obligation to its own citizens, to interpose its sovereignty against the unlawful federal actions, and to ultimately rescind its involvement in the federal compact and to thus secede from the Union if such action is ultimately required.

Summary

With regard to constitutional controls of the federal government, under our rule of law, the Constitution IS the controlling and limiting legal document of the federal government.

These limitations imposed on the federal government by the Constitution are unique controls imposed on the federal government and cannot be summarily and legally super-imposed back on the sovereign states by the federal government (e.g. the recent Second Amendment McDonald v Chicago SCOTUS decision).

Federal actions that are made and are subsequently found by the states to be outside the constitutionally mandated limitations imposed on the federal government by the Constitution, are null and void on their face, and the sovereign states are under no obligation to respond to, or perform according to these acts, but they are obligated to challenge and rescind unlawful acts of the federal government.

Regarding the Federalist Papers, there are many more references to the sovereignty and powers of the several states, but none support the idea that the states are offspring or children of, or are subservient to, the federal government, or that the United States is some kind of single ‘united state’ or nation.

Rather, as James Madison suggested, the states, while being part of the union, and even under extreme circumstances, retain their full and individual sovereignty, with the exception of the lawfully executed and limited powers delegated to the federal government.

As long as our country operates under our Rule of Law, the States and the people are sovereign, and they are always, and in all ways, sovereign over the powers of the federal government.

This is a critical time period in our American history when all of our sovereign states must step up to the task of challenging and ultimately controlling the errant and unlawful federal government as Arizona Governor Jan Brewer is doing in Arizona.

———————

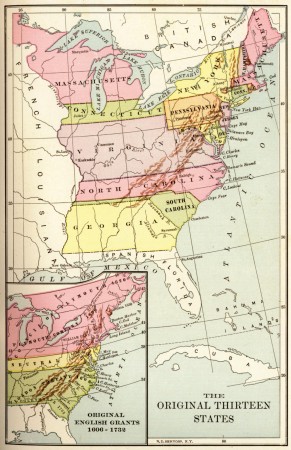

Editor’s Note: Many thanks to Paul McWhorter, who allowed The Post & Email to use his map of the original 13 colonies from his website.

Well, now that that is over and done with, all we need to do is to get the sovereign states to rein in and resume control of their out-of-control offspring – the federal government. But this is something they must do. And soon.

I would love to see the states control the federal government, as it would get rid of the great ‘normalizing’ effect emanating from the federal government, and let us actually see how the states run their states. With operational differences between the states allowed, open, and evident, we the people could then decide on which state to live and work.

This communism we live under now really stinks.

Freedom is a lovely thing. I miss it.